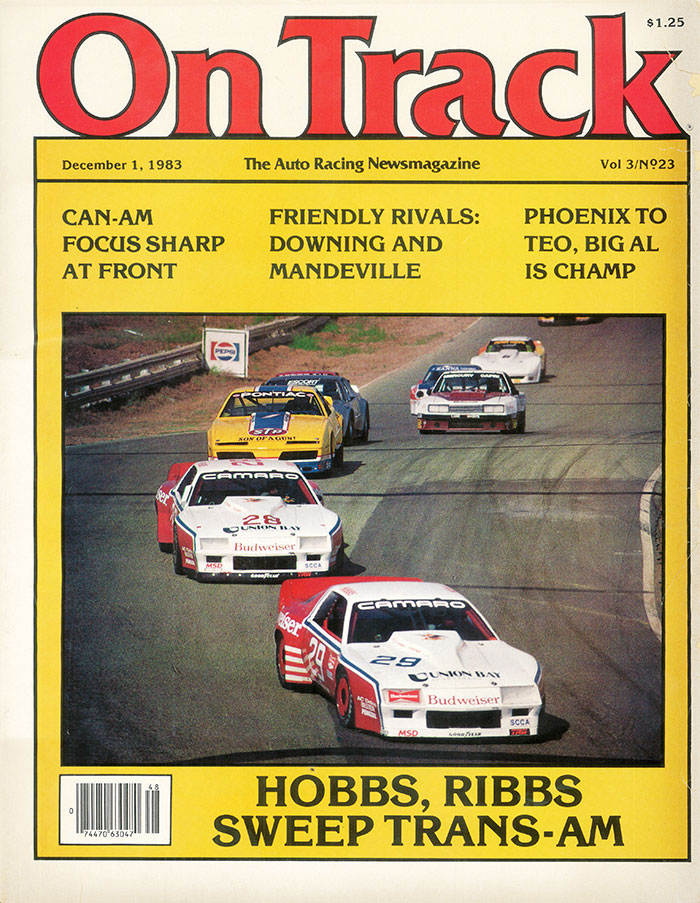

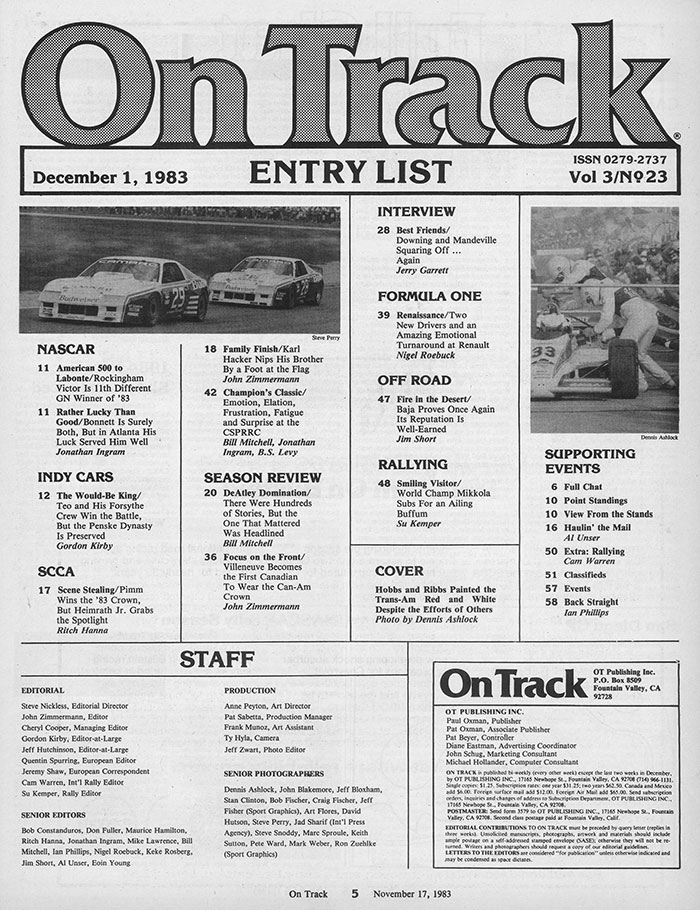

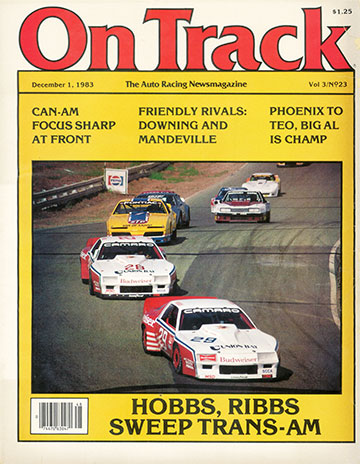

On Track

SEASON REVIEW

There Were Hundreds of Stories, Of Course, But the One That Mattered Most Was Headlined…

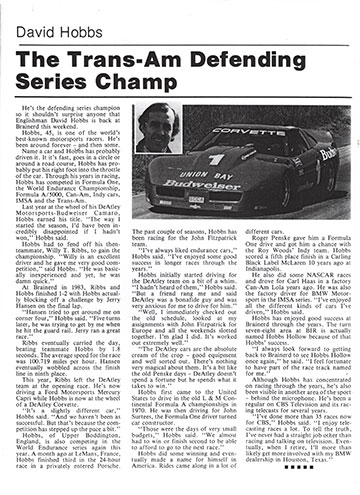

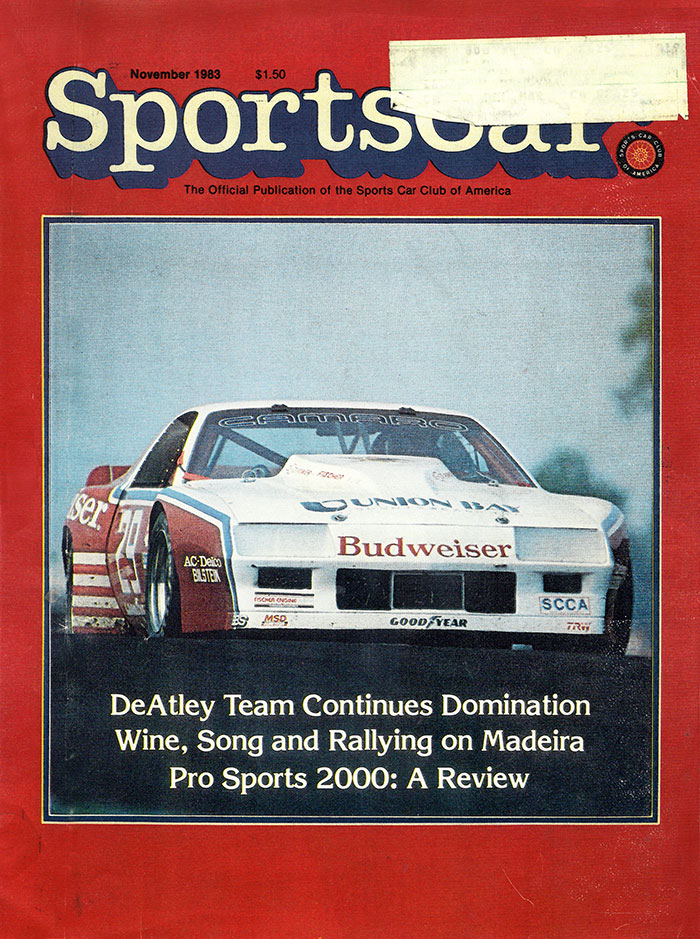

DeAtley Domination

TRANS-AM BUDWEISTER CHAMPIONSHIP

By Bill Mitchell

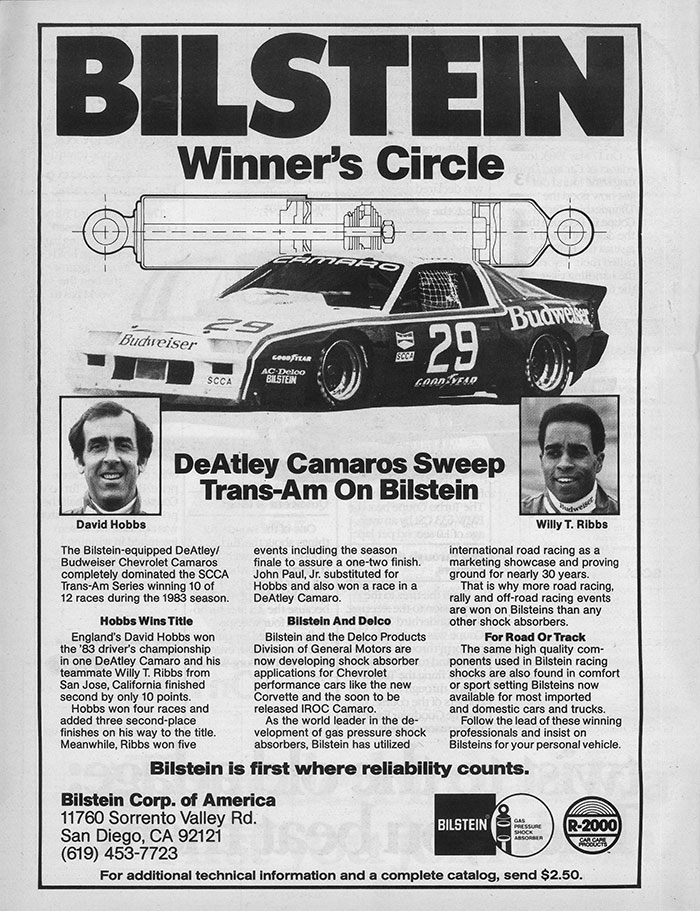

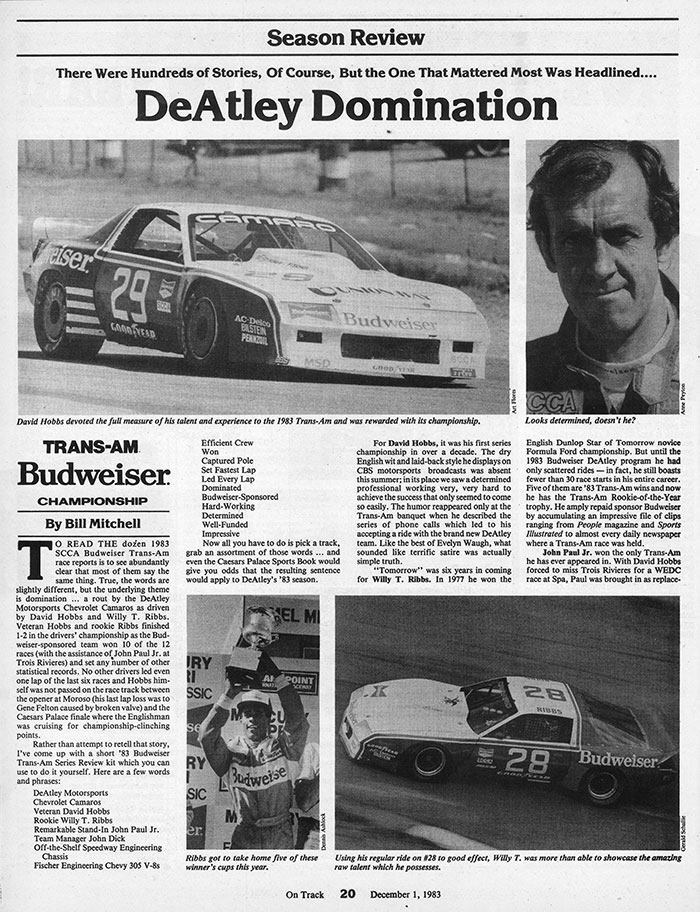

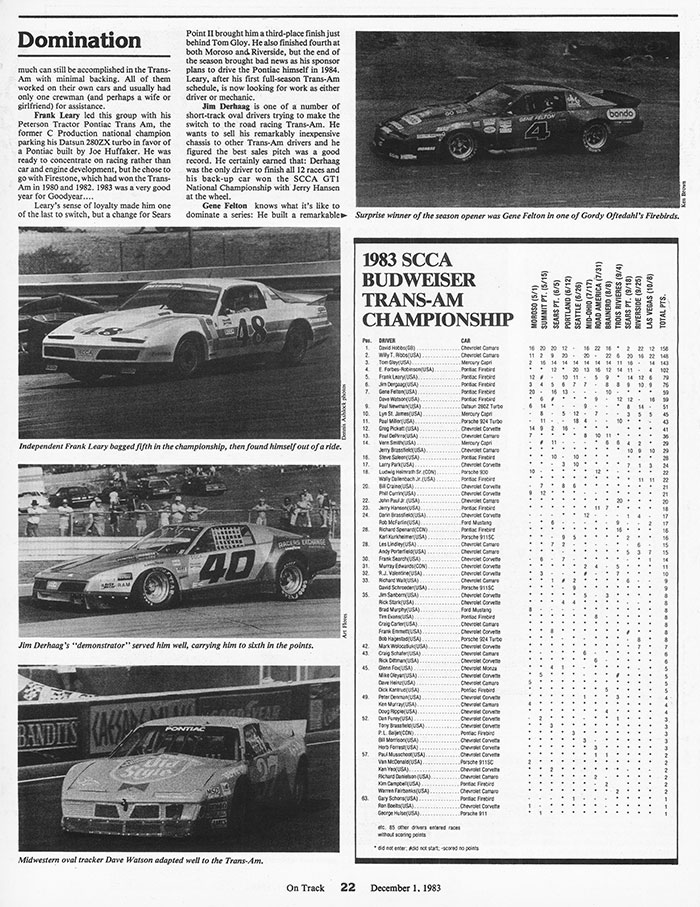

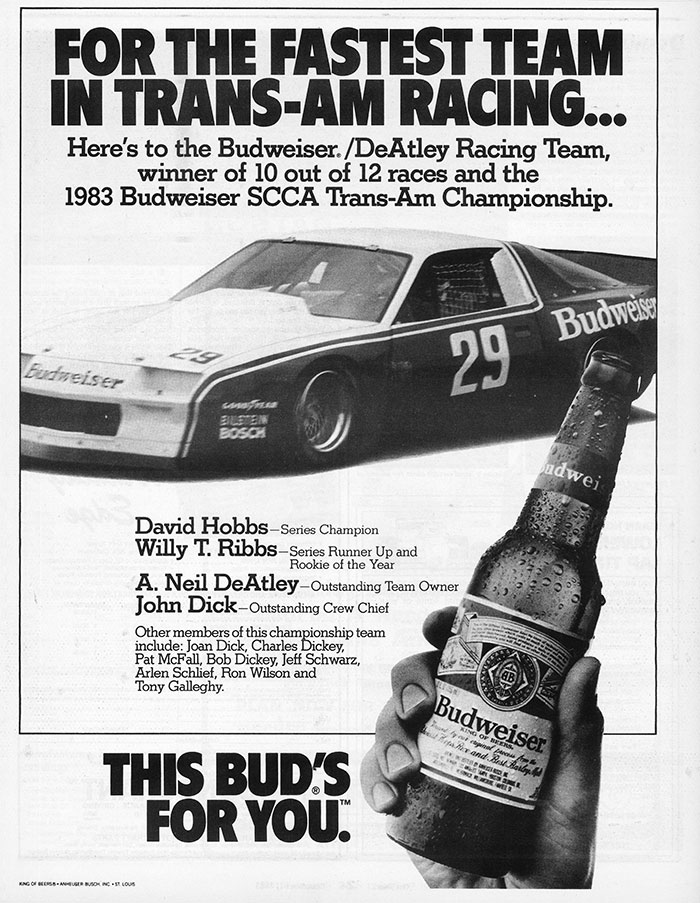

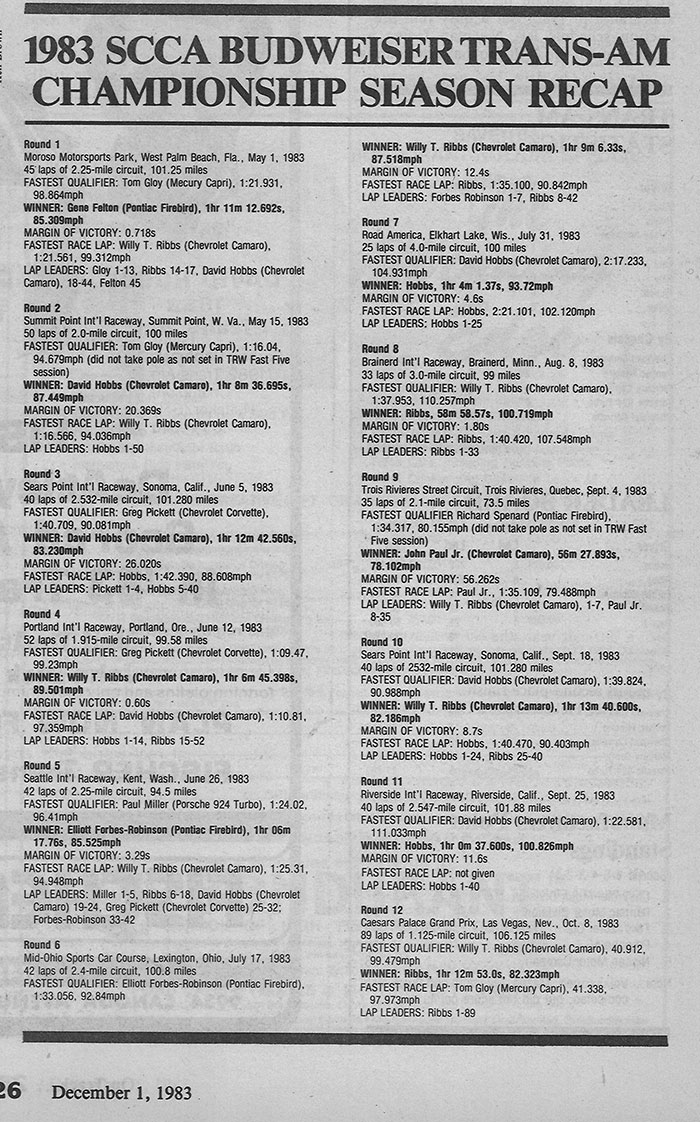

To read the dozen 1983 SCCA Budweiser Trans-Am race reports is to see abundantly clear that most of them say the same thing. True, the words are slightly different, but the underlying theme is domination … a rout by the DeAtley Motorsports Chevrolet Camaros as driven by David Hobbs and Willy T. Ribbs. Veteran Hobbs and rookie Ribbs finished 1-2 in the drivers’ championship as the Budweiser-sponsored team won 10 of the 12 races (with the assistance of John Paul Jr. at Trois Rivieres) and set any number of other statistical records. No other drivers led even one lap of the last six races and Hobbs himself was not passed on the race track between the opener at Moroso (his last lap loss was to Gene Felton caused by broken valve) and the Caesar’s Palace finale where the Englishman was cruising for championship-clinching points.

Rather than attempt to retell that story, I’ve come up with a short ’83 Budweiser Trans-Am Series Review kit which you can use to do it yourself. Here are a few words and phrases:

DeAtley Motorsports

Chevrolet Camaros

Veteran David Hobbs

Rookie Willy T. Ribbs

Remarkable Stand-in John Paul Jr.

Team Manager John Dick

Off-the Shelf Speedway Engineering Chassis

Fischer Engineering Chevy 305 V-8s

Efficient Crew

Won

Captured Pole

Set Fastest Lap

Led Every Lap

Dominated

Budweiser-Sponsored

Hard-Working

Determined

Well-Funded

Impressive

Now all you have to do is pick a track, grab an assortment of those words … and even the Caesars Palace Sports Book would give you odds that the resulting sentence would apply to DeAtley’s ’83 season.

For David Hobbs, it was his first series championship in over a decade. The dry English wit and laid-back style he displays on CBS motorsports broadcasts was absent this summer; in its place we saw a determined professional working very, very hard to achieve the success that only seemed to come so easily. The humor reappeared only at the Trans-Am banquet when he described the series of phone calls which led to his accepting a ride with the brand new DeAtley team. Like the best of Evelyn Waugh, what sounded like terrific satire was actually simple truth.

“Tomorrow” was six years in coming for Willy T. Ribbs. In 1977 he won the English Dunlop Star of Tomorrow novice Formula Ford Championship. But until the 1983 Budweiser DeAtley program he had only scattered rides – in fact, he still boasts fewer than 30 race starts in his entire career. Five of them are ’83 Trans-Am wins and now he has the Trans-Am Rookie-of-the-Year trophy. He amply repaid sponsor Budweiser by accumulating an impressive file of clips ranging from People magazine and Sports Illustrated to almost every daily newspaper where a Trans-Am race was held.

John Paul Jr. won the only Trans-Am he has ever appeared in. With David Hobbs forced to miss Trois Rivieres for a WEDC race at Spa, Paul was brought in as replacement. And he took the never-raced #30 DeAtley car to victory. We should not have been in the least bit surprised.

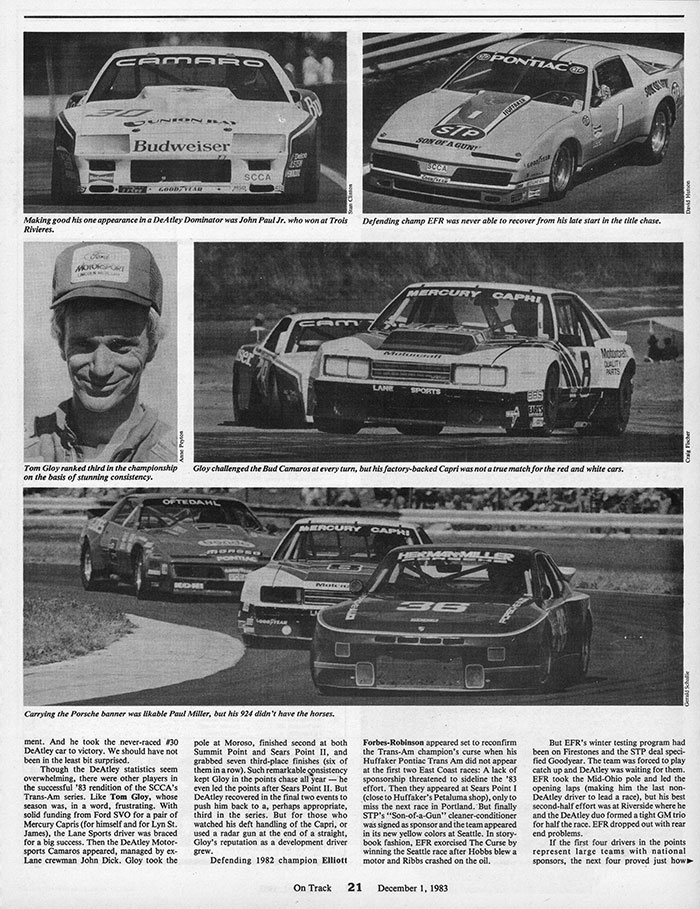

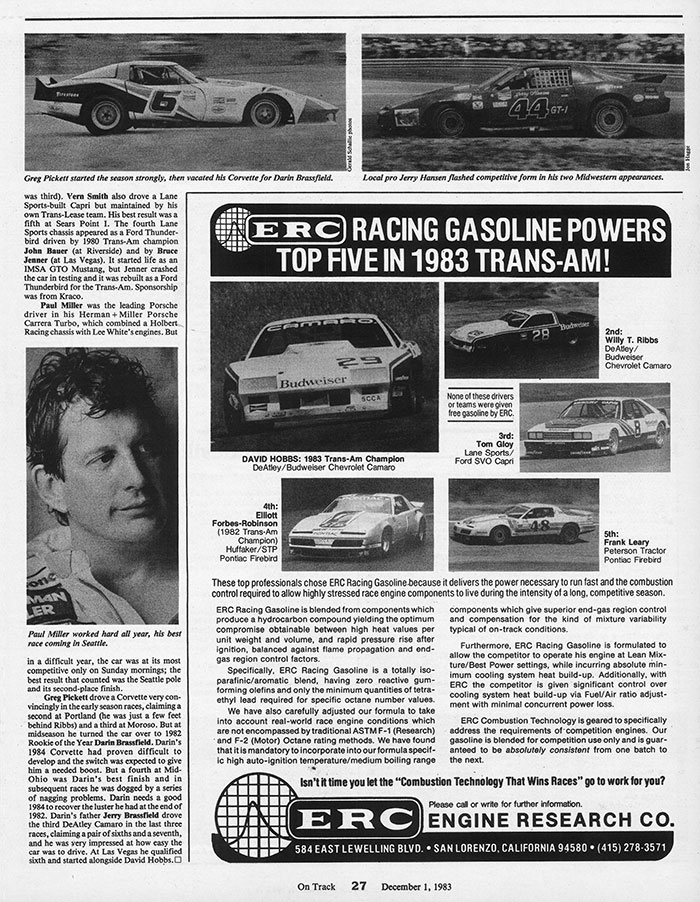

Though the DeAtley statistics seem overwhelming, there were other players in the successful ’83 rendition of the SCCA’s Trans-Am series. Like Tom Gloy, whose season was, in a word, frustrating. With solid funding from Ford SVO for a pair of Mercury Capris (for himself and for Lyn St. James), the Lane Sports driver was braced for a big success. Then the DeAtley Motorsports Camaros appeared, managed by ex-Lane crewman John Dick. Gloy took the pole at Moroso, finished second at both Summit Point and Sears Point II, and grabbed seven third-place finishes (six of them in a row). Such remarkable consistency kept Gloy in the points chase all year – he even led the points after Sears Point II. But DeAtley recovered in the final two events to push him back to a, perhaps appropriate, third in the series. But for those who watched his deft handling of the Capri, or used a radar gun at the end of a straight, Gloy’s reputation as a development driver grew.

Defending 1982 champion Elliot Forbes-Robinson appeared set to reconfirm the Trans-Am champion’s curse when his Huffaker Pontiac Trans Am did not appear at the first two East Coast races: A lack of sponsorship threatened to sideline the ’83 effort. Then they appeared at Sears Point I (close to Huffaker’s Petaluma shop), only to miss the next race at Portland. But finally STP’s “Son-of-a-Gun” cleaner-conditioner was signed as sponsor and the team appeared in its new yellow colors at Seattle. In storybook fashion, EFR exorcised The Curse by winning the Seattle race after Hobbs blew a motor and Ribbs crashed on the oil.

But EFR’s winter testing program had been on Firestones and the STP deal specified Goodyear. The team was forced to play catch up and DeAtley was waiting for them. EFR took the Mid-Ohio pole and led the opening laps (making him the last non-DeAtley driver to lead a race), but his best second-half effort was at Riverside where he and the DeAtley duo formed a tight GM trio for half the race. EFR dropped out with rear end problems.

If the first four drivers in the points represent large teams with national sponsors, the next four proved just how much can be accomplished in the Trans-Am with minimal backing. All of them worked on their own cars and usually had only one crewman (and perhaps a wife or girlfriend) for assistance.

Frank Leary led this group with his Peterson Tractor Pontiac Trans Am, the former C Production national champion parking his Datsun 280ZX turbo in favor of a Pontiac built by Joe Huffaker. He was ready to concentrate on racing rather than car and engine development, but he chose to go with Firestone, which had won the Trans-Am in 1980 and 1982. 1983 was a very good year for Goodyear….

Leary’s sense of loyalty made him one of the last to switch, but a change for Sears Point II brought him a third-place finish just behind Tom Gloy. He also finished fourth at both Moroso and Riverside, but the end of the season brought bad news as his sponsor plans to drive the Pontiac himself in 1984. Leary, after his first full-season Trans-Am schedule, is now looking for work as either driver or mechanic.

Jim Derhaag is one of a number of short-track oval drivers trying to make the switch to the road-racing Trans-Am. He wants to sell his remarkably inexpensive chassis to other Trans-Am drivers and he figured the best sales pitch was a good record. He certainly earned that: Derhaag was the only driver to finish all 12 races and his back-up car won the SCCA GT1 National Championship with Jerry Hansen at the wheel.

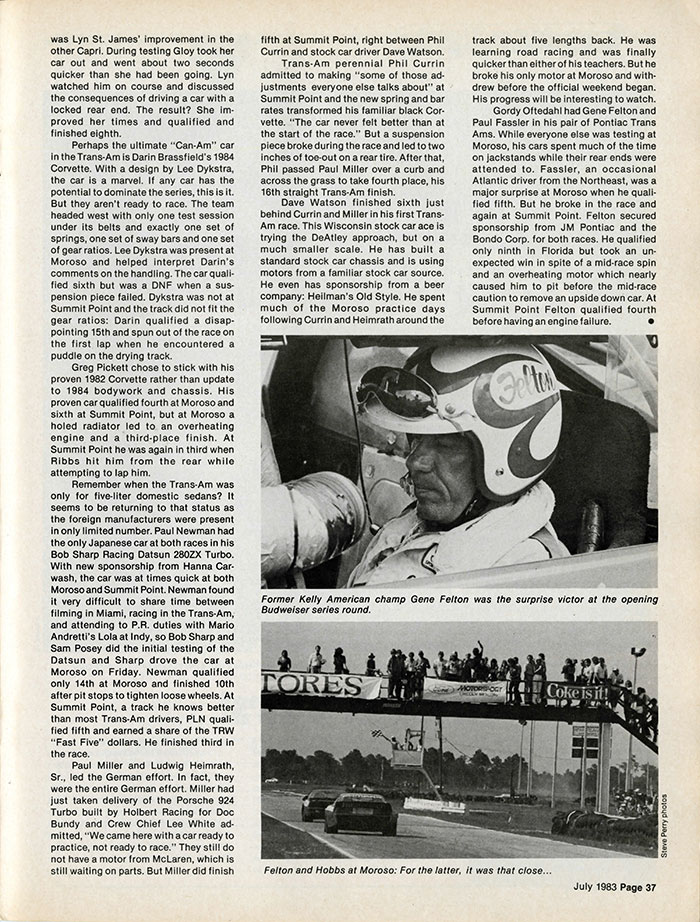

Gene Felton knows what it’s like to dominate a series: He built a remarkable string of consecutive wins in the process of claiming four Kelly-American championships. The ’83 Moroso opener was his first Trans-Am race and throughout most of the weekend his Oftedahl Trans Am was over shadowed by the DeAtley and Lane Sport cars. But he scored an amazing victory by passing David Hobbs on the last lap. He had been closing on an ailing Hobbs by more than a second a lap but looked to be out of time. Then he erased more than a second on the final lap, passed on the wide back straight (where he carefully stayed out of Hobb’s mirrors), and led through the final two turns. He is still surprised he was able to pull it off. Unfortunately, the remainder of Gene’s season involved trying to stretch his limited Bondo sponsorship as far as it would go. Felton finished second at Sears Point I and claimed the pole at Portland, but soon thereafter the money ran out and he left the series after Brainerd.

Dave Watson is another short-track oval star to join the Trans-Am. His Heilmann’s Old Style Pontiac traveled on an open trailer behind a van, and Watson started the season assuming his driving talent could bridge the dollar gap between his effort and the DeAtley type. He quickly discovered that in road racing the straights are long enough that a mule motor simply won’t get the job done. A crash at Sears Point I while trying for the one demon qualifying lap forced him to re-evaluate again. After that came steady improvement. At Trois Rivieres and Sears Point II he finished fourth. At Caesars Palace he finally found a track where he had as much experience as any other Trans-Am driver and that advantage, coupled with his oval-track knowledge, produced an impressive performance. He qualified fourth (in the TRW Fast Five) and ran a steady second in the race. Watson was closing rapidly in the final laps as his tires had a lot more life left, but he needed another 30 miles to pass Ribbs. His first victory will have to wait for ’84.

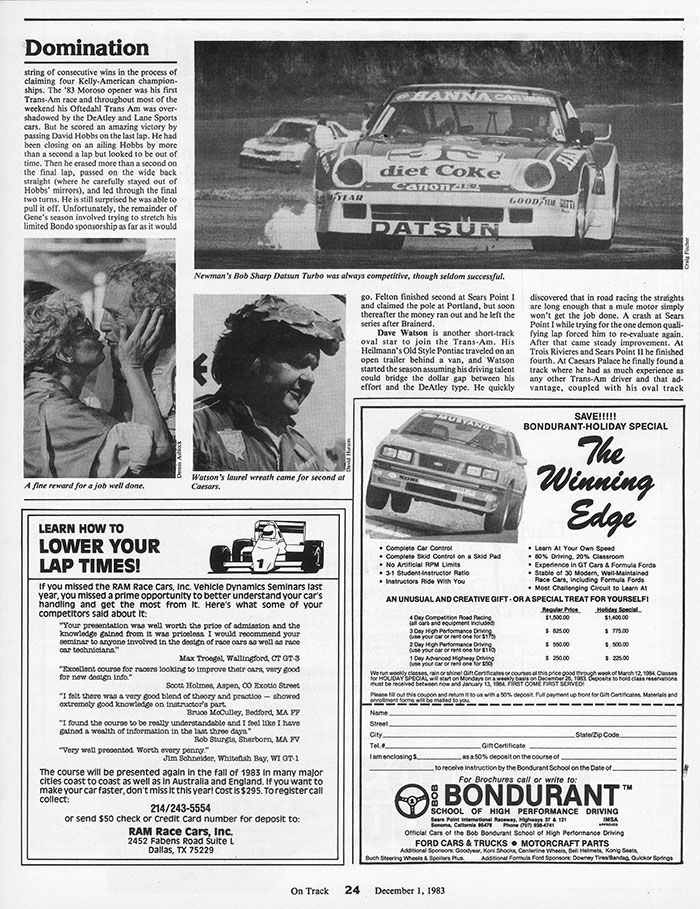

Paul Newman and his Bob Sharp Racing Division Datsun 280ZX Turbo had a very frustrating and disappointing season. Their Diet Coke and Hanna Car Wash sponsorship ranked with the Budweiser and Ford Motor Co deals and no one doubts the ability of Gene Crowe or the Bob Sharp Racing crew. Newman long ago proved himself a capable driver; like John Paul Jr. in 1983, he won in his only Trans-Am appearance in 1982. But a busy film production schedule left Newman facing a number of red-eye flights to make races and much of the racing was left to Sam Posey. In the races there were a number of mechanical problems and Newman’s best results were a pair of thirds at Summit Point and Riverside. Next year the team faces the challenge of developing a 300ZX Turbo with both a new chassis and new engine.

Lyn St. James drove the second Lane Sports Mercury Capri to 10th in the series. Her best finish was a fourth at Seattle (Gloy was third). Vern Smith also drove a Lane Sports-built Capri but maintained by his own Trans-Lease team. His best result was a fifth at Sears Point I. The fourth Lane Sports chassis appeared as a Ford Thunderbird driven by 1980 Trans-Am champion John Bauer (at Riverside) and by Bruce Jenner (at Las Vegas). It started life as an IMSA GTO Mustang, but Jenner crashed the car in testing and it was rebuilt as a Ford Thunderbird for the Trans-Am. Sponsorship was from Kraco.

Paul Miller was the leading Porsche driver in his Herman + Miller Porsche Carrera Turbo, which combined a Holbert racing chassis with Lee White’s engines. But in a difficult year, the car was at its most competitive only on Sunday mornings; the best result that counted was the Seattle pole and its second-place finish.

Greg Pickett drove a Corvette very convincingly in the early season races, claiming a second at Portland (he was just a few feet behind Ribbs) and a third at Moroso. But at midseason he turned the car over to 1982 Rookie-of-the-Year Darin Brassfield. Darin’s 1984 Corvette had proven difficult to develop and the switch was expected to give him a needed boost. But a fourth at Mid-Ohio was Darin’s best finish and in subsequent races he was dogged by a series of nagging problems. Darin needs a good 1984 to recover the luster he had at the end of 1982. Darin’s father Jerry Brassfield drove the third DeAtley Camaro in the last three races, claiming a pair of sixths and a seventh, and he was very impressed at how easy the car was to drive. At Las Vegas he qualified sixth and started alongside David Hobbs.

Without DeAtley

The domination of the DeAtley Motorsports team of Budweiser Camaros was so overwhelming, it left everyone wondering what the 1983 Trans-Am series would have been like without them. The following is what might have been. It is, of course, impossible to “accurately” reconstruct history because the other teams made decisions in ’83 based on the presence of DeAtley. Without Hobbs and Ribbs to chase, Tom Gloy would probably not have tried that new motor at Riverside. Thus he might have avoided his only engine failure of the year. We’ll never know.

Moroso: Tom Gloy takes the pole but breaks a hub while leading. Greg Pickett inherits the lead in his Corvette, only to be slowed by overheating. Gene Felton recovers from a spin to take the win in Gordy Oftedahl’s Pontiac Trans Am. Pickett is second and Frank Leary third in his new Pontiac.

Summit Point: Gloy again puts his Mercury Capri on the pole, but Greg Pickett wins in his Corvette. (In reality, Pickett tangled with Ribbs as the DeAtley pair nearly lapped the field. But with the imaginary elimination of Ribbs, we give the race to Pickett ahead of Gloy and Paul Newman).

Sears Point: Pickett takes the pole, but an unexpectedly hot day causes tire problems for Greg, Gloy and Elliott Forbes-Robinson. Felton again comes from a distant grid position to take his second win of the year. Gloy is second for the third consecutive race; Forbes-Robinson third.

Portland: Felton takes the pole in damp conditions, but Pickett wins the race, finishing ahead of Gloy, Felton and Leary.

Seattle: In this race the DeAtley pair really did eliminate themselves, so … EFR wins, finishing ahead of polesitter Paul Miller and Gloy.

Mid-Ohio: Forbes-Robinson takes the pole, but Gloy wins on a track ideally suited to the handling qualities of his Capri. Darin Brassfield is second in a 1982 Corvette, ahead of EFT.

Road America: Forbes-Robinson wins from the pole, finishing over Gloy and Ludwig Heimrath Sr.’s Porsche 930. The Elkhart Lake track seems ideally suited to turbo Porsches.

Brainerd: Jerry Hanson wins on home turf with an impressive charge through the pack. (Since he didn’t have David Hobbs to pass him on the final lap in this story, we give him the win in his Firebird.) Gloy takes second from polesitter EFR on the final lap.

Trois Rivieres: Richard Spenard takes enormously popular victory through the streets to give Quebec natives a Can-Am/Trans-Am sweep. Polesitter EFR is second ahead of Dave Watson and Gloy. Gloy had been leading when his right front wheel came off, requiring a pit stop.

Sears Point II: Gloy returns to his home ground to take his third straight fall Sears Point victory. The tight track favored the Capri and Gloy wins in spite of a tire change midrace. Leary is a close second at the finish and Watson is again third.

Riverside: Newman brings the Datsun 280ZX Turbo home a winner after polesitter EFR suffers a rear end failure while leading. Leary is again second and Wally Dallenbach Jr. is third in his first Trans-Am.

Caesars Palace: Watson wins the season finale on Las Vegas’ “oval” after polesitter Gloy again makes a pit stop to replace a blistered tire. Gloy is second for the sixth time, but he wraps up the championship handily. EFR is a distant second in the points.

This imaginary season produces eight different race winners with no one claiming more than two victories. Gloy, EFR, Pickett and Felton were all two-time winners; Jerry Hansen, Richard Spenard, Paul Newman and Dave Watson won single races. Pontiac takes the Manufacturer’s championship with seven victories and two seconds. Ford is second with two wins and two seconds.

This is what most people expected the 1983 Trans-Am to be: a highly competitive season where the champion would be determined by a few wins and consistent high finishings. The real 1983 Trans-Am had the tight points chase, but the DeAtley Motorsports team dominated the win column with 10 victories. Which way will 1984 go?

Bill Mitchell

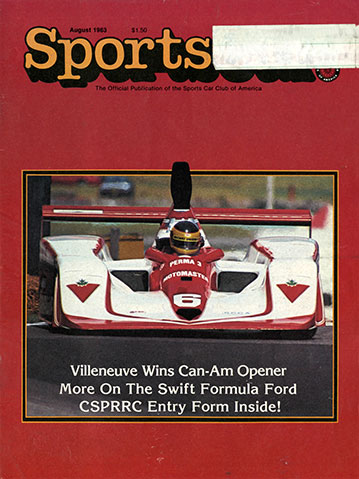

SportsCar

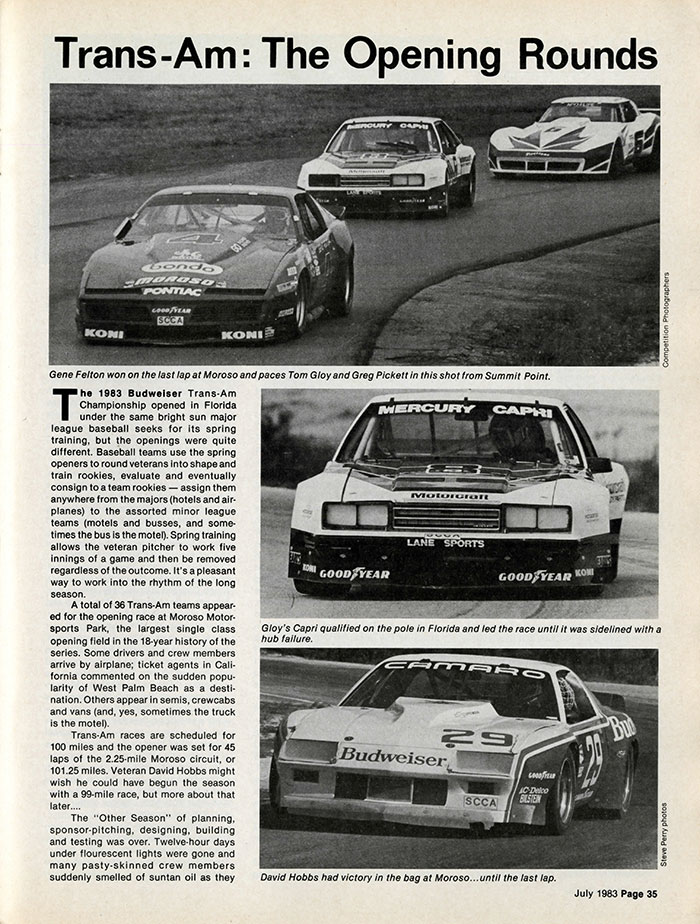

Trans-Am: The Opening Rounds

The 1983 Budweiser Trans-Am Championship opened in Florida under the same bright sun major league baseball seeks for its spring training, but the openings were quite different. Baseball teams use the spring openers to round veterans into shape and train rookies, evaluate and eventually consign to a team rookies – assign them anywhere from the majors (hotels and airplanes) to the assorted minor league teams (motels and buses, and sometimes the bus is the motel). Spring training allows the veteran pitcher to work five innings of a game and then be removed regardless of the outcome. It’s a pleasant way to work into the rhythm of the long season.

A total of 36 Trans-Am teams appeared for the opening race at Moroso Motorsports Park, the largest single class opening field in the 18-year history of the series. Some drivers and crew members arrive by airplane; ticket agents in California commented on the sudden popularity of West Palm Beach as a destination. Others appear in semis, crewcabs and vans (and, yes sometimes the truck is the motel).

Trans-Am races are scheduled for 100 miles and the opener was set for 45 laps of the 2.25-mile Moroso circuit, or 101.25 miles. Veteran David Hobbs might wish he could have begun the season with a 99-mile race, but more about that later…

The “Other Season” of planning, sponsor-pitching, designing, building and testing was over. Twelve-hour days under fluorescent lights were gone and many pasty-skinned crew members suddenly smelled of suntan oil as they began a summer of 12-hour days in the sun. It was time to offer for public inspection and criticism the product of the “Other Season.” And then driver, car and crew were subjected to the unforgiving test of a race. Some were ready and some were not.

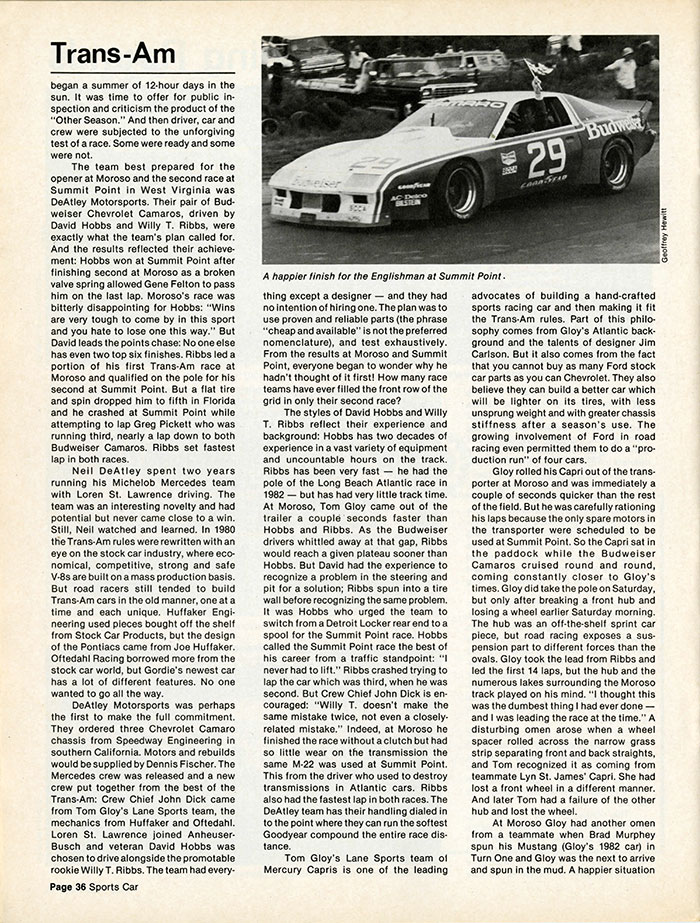

The team best prepared for the opener at Moroso and the second race at Summit Point in West Virginia was DeAtley Motorsports. Their pair of Budweiser Chevrolet Camaros, driven by David Hobbs and Willy T. Ribbs, were exactly what the team’s plan called for. And the results reflected their achievement: Hobbs won at Summit Point after finishing second at Moroso as a broken valve spring allowed Gene Felton to pass him on the last lap. Moroso’s race was bitterly disappointing for Hobbs: “Wins are very tough to come by in this sport and you hate to lose one this way.” But David leads the points chase. No one else has even two top six finishes. Ribbs led a portion of his first Trans-Am race at Moroso and qualified on the pole for his second at Summit Point. But a flat tire and spin dropped him to fifth in Florida and he crashed at Summit Point while attempting to lap Greg Pickett who was running third, nearly a lap down to both Budweiser Camaros. Ribbs set fastest lap in both races.

Neil DeAtley spent two years running his Michelob Mercedes team with Loren St. Lawrence driving. The team was an interesting novelty and had potential but never came close to a win. Still, Neil watched and learned. In 1980 the Trans-Am rules were rewritten with an eye on the stock car industry, where economical, competitive, strong and safe V-8s are built on a mass production basis. But road racers still tended to build Trans-Am cars in the old manner, one at a time and each unique. Huffaker Engineering used pieces bought off the shelf from Stock Car products, but the design of Pontiacs came from Joe Huffaker. Oftedahl Racing borrowed more from the stock car world, but Gordie’s newest car has a lot of different features. No one wanted to go all the way.

DeAtley Motorsports was perhaps the first to make the full commitment. They ordered three Chevrolet Camaro chassis from Speedway Engineering in southern California. Motors and rebuilds would be supplied by Dennis Fischer. The Mercedes crew was released and a new crew put together from the best of the Trans-Am. Crew Chief John Dick came from Tom Gloy’s Lane Sports Team, the mechanics from Huffaker and Oftedahl. Loren St. Lawrence joined Anheuser-Busch and veteran David Hobbs was chosen to drive alongside the promotable rookie Willy T. Ribbs. The team had everything except a designer – and they had no intention of hiring one. The plan was to use proven and reliable parts (the phrase “cheap and available” is not the preferred nomenclature), and test exhaustively. From the results at Moroso and Summit Point, everyone began to wonder why he hadn’t thought of it first! How many race teams have ever filled the front row of the grid in only their second race?

The styles of David Hobbs and Willy T. Ribbs reflect their experience and background: Hobbs has two decades of experience in a vast variety of equipment and uncountable hours on the track. Ribbs has been very fast – he had the pole of the Long Beach Atlantic race in 1982 – but has had very little track time. At Moroso, Tom Gloy came out of the trailer a couple seconds faster than Hobbs and Ribbs. As the Budweiser drivers whittled away at that gap, Ribbs would reach a given plateau sooner than Hobbs. But David had the experience to recognize a problem in the steering and pit for a solution; Ribbs spun into a tire wall before recognizing the same problem.

It was Hobbs who urged the team to switch from a Detroit Locker rear end to a spool for the Summit Point race. Hobbs called the Summit Point race the best of his career from a traffic standpoint: “I never had to lift.” Ribbs crashed trying to lap the car which was third, when he was second. But Crew Chief John Dick is encouraged: “Willy T. doesn’t make the same mistake twice, not even a closely-related mistake.” Indeed, at Moroso he finished the race without a clutch but had so little wear on the transmission the same M-22 was used at Summit Point. This from the driver who used to destroy transmissions in Atlantic cars. Ribbs also had the fastest lap in both races. The DeAtley team has their handling dialed in to the point where they can run the softest Goodyear compound the entire race distance.

Tom Gloy’s Lane Sports team of Mercury Capris is one of the leading advocates of building a hand-crafted sports racing car and then making it fit the Trans-Am rules. Part of this philosophy comes from Gloy’s Atlantic background and the talents of designer Jim Carlson. But it also comes from the fact that you cannot buy as many Ford stock car parts as you can Chevrolet. They also believe they can build a better car which will be lighter on its tires, with less unsprung weight and with greater chassis stiffness after a season’s use. The growing involvement of Ford in road racing even permitted them to do a “production run” of four cars.

Gloy rolled his Capri out of the transporter at Moroso and was immediately a couple of seconds quicker than the rest of the field. But he was carefully rationing his laps because the only spare motors in the transporter were scheduled to be used at Summit Point. So the Capri sat in the paddock while the Budweiser Camaros cruised round and round, coming constantly closer to Gloy’s times. Gloy did take the pole on Saturday, but only after breaking a front hub and losing a wheel earlier Saturday morning. The hub was an off-the-shelf sprint car piece, but road-racing exposes a suspension part to different forces than the ovals. Gloy took the lead from Ribbs and led the first 14 laps, but the hub and the numerous lakes surrounding the Moroso track played on his mind. “I thought this was the dumbest thing I had ever done – and I was leading the race at the time.” A disturbing omen arose when a wheel spacer rolled across the narrow grass strip separating front and back straights, and Tom recognized it as coming from teammate Lyn St. James’ Capri. She had lost a front wheel in a different manner. And later Tom had a failure of the other hub and lost the wheel.

At Moroso Gloy had another omen from a teammate when Brad Murphey spun his Mustang (Gloy’s 1982 car) in Turn One and Gloy was the next to arrive and spun in the mud. A happier situation was Lyn St. James’ improvement in the other Capri. During testing Gloy took her car out and went about two seconds quicker than she had been going. Lyn watched him on course and discussed the consequences of driving a car with a locked rear end. The result? She improved her times and qualified and finished eighth.

Perhaps the ultimate “Can-Am” car in the Trans-Am is Darin Brassfield’s 1984 Corvette. With a design by Lee Dykstra, the car is a marvel. If any car has the potential to dominate the series, this is it. But they aren’t ready to race. The team headed west with only one test session under its belts and exactly one set of springs, one set of sway bars and one set of gear ratios. Lee Dykstra was present at Moroso and helped interpret Darin’s comments on the handling. The car qualified sixth but was a DNF when a suspension piece failed. Dykstra was not at Summit Point and the track did not fit the gear ratios: Darin qualified a disappointing 15th and spun out of the race on the first lap when he encountered a puddle on the drying track.

Greg Pickett chose to stick with his proven 1982 Corvette rather than update to 1984 bodywork and chassis. His proven car qualified fourth at Moroso and sixth at Summit Point, but at Moroso a holed radiator led to an overheating engine and a third-place finish. At Summit Point he was again in third when Ribbs hit him from the rear while attempting to lap him.

Remember when the Trans-Am was only for five-liter domestic sedans? It seems to be returning to that status as the foreign manufacturers were present in only limited number. Paul Newman had the only Japanese car at both races in his Bob Sharp Racing Datsun 280ZX Turbo. With new sponsorship from Hanna Carwash, the car was at times quick at both Moroso and Summit Point. Newman found it very difficult to share time between filming in Miami, racing in the Trans-Am, and attending to P.R. duties with Mario Andretti’s Lola at Indy, so Bob Sharp and Sam Posey did the initial testing of the Datsun and Sharp drove the car at Moroso on Friday. Newman qualified only 14th at Moroso and finished 10th after pit stops to tighten loose wheels. At Summit Point, a track that he knows better than most Trans-Am drivers, PLN qualified fifth and earned a share of the TRW “Fast Five” dollars. He finished third in the race.

Paul Miller and Ludwig Heimrath, Sr., led the German effort. In fact, they were the entire German effort. Miller had just taken delivery of the Porsche 924 Turbo built by Holbert Racing for Doc Bundy and Crew Chief Lee White admitted, “We came here with a car ready to practice, not ready to race.” They still do not have a motor from McLaren, which is still waiting on parts. But Miller did finish fifth at Summit Point, right between Phil Currin and stock car driver Dave Watson.

Trans-Am perennial Phil Currin admitted to making “some of those adjustments everyone else talks about” at Summit Point and the new spring and bar rates transformed his familiar black Corvette. “The car never felt better than at the start of the race.” But a suspension piece broke during the race and led to two inches of toe-out on a rear tire. After that, Phil passed Paul Miller over a curb and across the grass to take fourth place, his 16th straight Trans-Am finish.

Dave Watson finished sixth just behind Currin and Miller in his first Trans-Am race. The Wisconsin stock car ace is trying the DeAtley approach, but on a much smaller scale. He has built a standard stock car chassis and is using motors from a familiar stock car source. He even had sponsorship from a beer company: Heilman’s Old Style. He spent much of the Moroso practice days following Currin and Heimrath around the track about five lengths back. He was learning road racing and was finally quicker than either of his teachers. But he broke his only motor at Moroso and withdrew before the official weekend began. His progress will be interesting to watch.

Gordy Oftedahl had Gene Felton and Paul Fassler in his pair of Pontiac Trans Ams. While everyone else was testing at Moroso, his cars spent much of the time on jackstands while their rear ends were attended to. Fassler, an occasional Atlantic driver from the Northeast, was a major surprise at Moroso when he qualified fifth. But he broke in the race and again at Summit Point. Felton secured sponsorship from JM Pontiac and the Bondo Corp. for both races. He qualified only ninth in Florida but took an unexpected win in spite of a mid-race spin and an overheating motor which nearly caused him to pit before the mid-race caution to remove an upside-down car. At Summit Point Felton qualified fourth before having an engine failure.

On Track

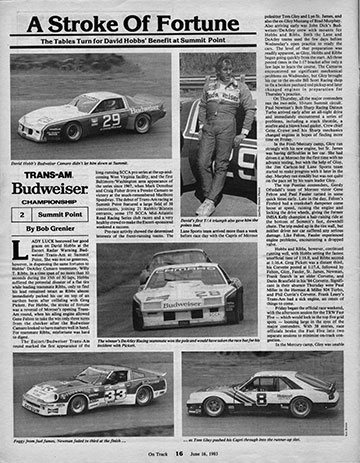

A Stroke of Fortune

The Tables Turn for David Hobbs’ Benefit at Summit Point

TRANS-AM BUDWEISER

CHAMPIONSHIP

Summit Point

June 16, 1983

By Bob Frenier

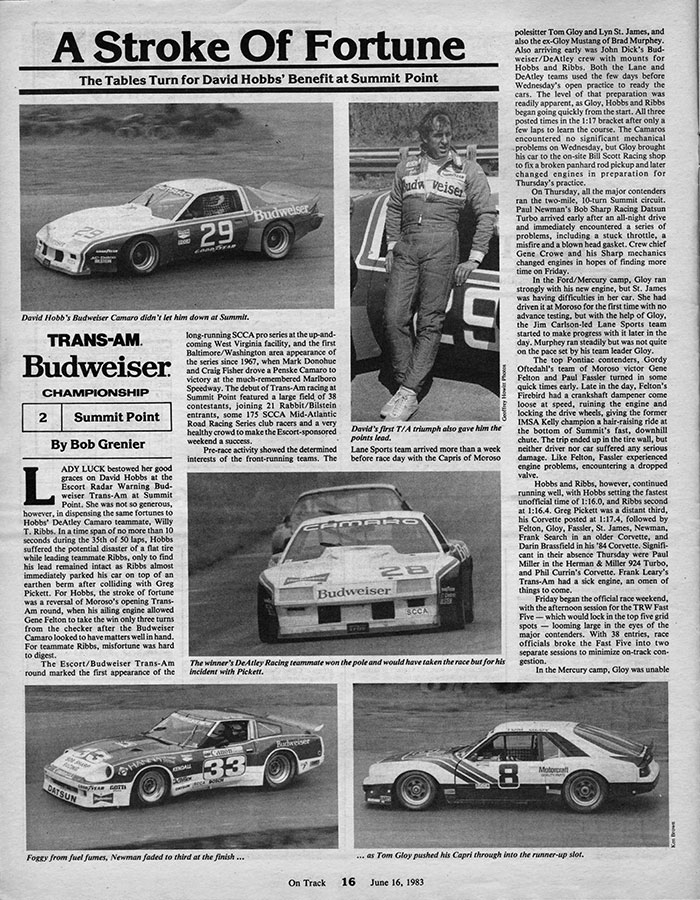

Lady Luck bestowed her good graces on David Hobbs at the Escort Radar Warning Budweiser Trans-Am at Summit Point. She was not so generous, however, in dispensing the same fortunes to Hobbs’ DeAtley Camaro teammate, Willy T. Ribbs. In a time span of no more than 10 seconds during the 35th of 50 laps, Hobbs suffered the potential disaster of a flat tire while leading teammate Ribbs, only to find his lead remained intact as Ribbs almost immediately parked his car on top of an earthen berm after colliding with Greg Pickett. For Hobbs, the stroke of fortune was a reversal of Moroso’s opening Trans-Am round, when his ailing engine allowed Gene Felton to take the win only three turns from the checker after the Budweiser Camaro looked to have matters well in hand. For teammate Ribbs, misfortune was hard to digest.

The Escort/Budweiser Trans-Am round marked the first appearance of the long-running SCCA pro series at the up-and-coming West Virginia facility, and the first Baltimore/Washington area appearance of the series since 1967, when Mark Donohue and Craig Fisher drove a Penske Camaro to victory at the much-remembered Marlboro Speedway. The debut of Trans-Am racing at Summit Point featured a large field of 38 contestants, joining 21 Ribbit/Bilstein entrants, some 175 SCCA Mid-Atlantic Road Racing Series club racers and a very healthy crowd to make the Escort-sponsored weekend a success.

Pre-race activity showed the determined interests of the front-running teams. The Lane Sports team arrived more than a week before race day with the Capris of Moroso polesitter Tom Gloy and Lyn St. James, and also the ex-Gloy Mustang of Brad Murphey. Also arriving early was John Dick’s Budweiser/DeAtley crew with mounts for Hobbs and Ribbs. Both the Lane and DeAtley teams used the few days before Wednesday’s open practice to ready the cars. The level of that preparation was readily apparent, as Gloy, Hobbs and Ribbs began going quickly from the start. The Camaros encountered no significant mechanical problems on Wednesday, but Gloy brought his car to the on-site Bill Scott Racing shop to fix a broken panhard rod pickup and later changed engines in preparation for Thursday’s practice.

On Thursday, all the major contenders ran the two-mile, 10-turn Summit circuit. Paul Newman’s Bob Sharp Racing Datsun Turbo arrived early after an all-night drive and immediately encountered a series of problems, including a stuck throttle, a misfire, and a blown head gasket. Crew chief Gene Crowe and his Sharp mechanics changed engines in hopes of finding more time on Friday.

In the Ford/Mercury camp, Gloy ran strongly with his new engine, but St. James was having difficulties in her car. She had driven it at Moroso for the first time with no advance testing, but with the help of Gloy, the Jim Carlson-led Lane Sports team started to make progress with it later in the day. Murphey ran steadily but was not quite on the pace set by his team leader Gloy.

The top Pontiac contenders, Gordy Oftedahl’s team of Moroso victor Gene Felton and Paul Fassler turned in some quick times early. Late in the day, Felton’s Firebird had a crankshaft dampener come loose at speed, ruining the engine and locking the drive wheels, giving the former IMSA Kelly champion a hair-raising ride at the bottom of Summit’s fast, downhill chute. The trip ended up in the tire wall, but neither driver nor car suffered any serious damage. Like Felton, Fassler experienced engine problems, encountering a dropped valve.

Hobbs and Ribbs, however, continued running well, with Hobbs setting the fastest unofficial time of 1:16.0, and Ribbs second at 1:16.4. Greg Pickett was a distant third, his Corvette posted at 1:17.4, followed by Felton, Gloy, Fassler, St. James, Newman, Frank Search in an older Corvette, and Darin Brassfield in his ’84 Corvette. Significant in their absence Thursday were Paul Miller in the Herman & Miller 924 Turbo, and Phil Currin’s Corvette. Frank Leary’s Trans-Am had a sick engine, on omen of things to come.

Friday began the official race weekend, with the afternoon session for the TRW Fast Five – which would lock in the top five grid spots – looming large in the eyes of the major contenders. With 38 entries, race officials broke the Fast Five into two separate sessions to minimize on-track congestion.

SportsCar

Competiton Update

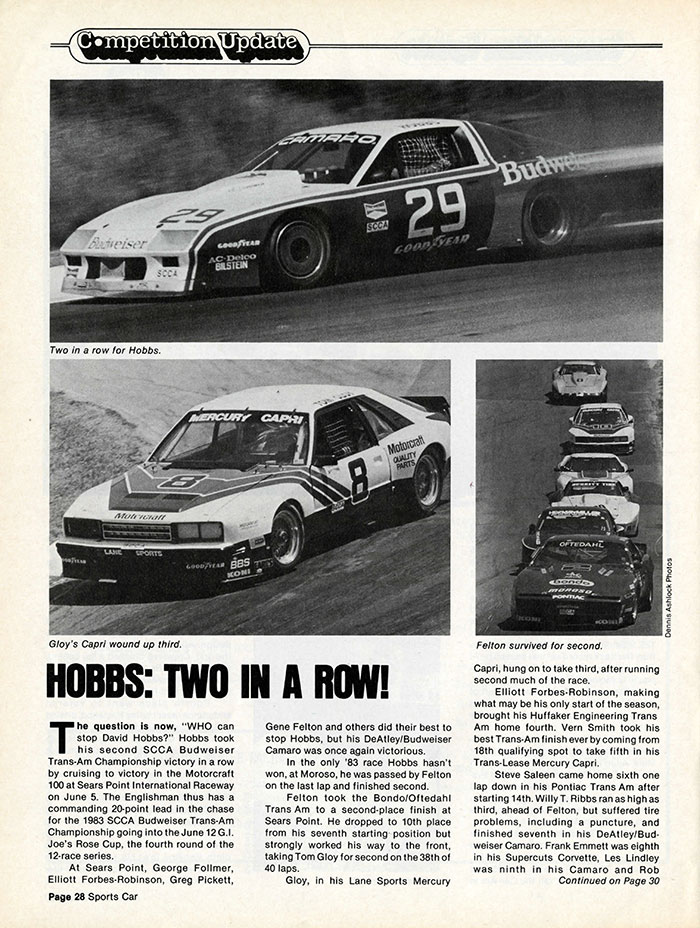

HOBBS: TWO IN A ROW!

The question is now, “WHO can stop David Hobbs?” Hobbs took his second SCCA Budweiser Trans-Am Championship victory in a row by cruising to victory in the Motorcraft 100 at Sears Point International Raceway on June 5. The Englishman thus has a commanding 20-point lead in the chase for the 1983 Budweiser Trans-Am Championship going into the June 12 G.I. Joe’s Rose Cup, the fourth round of the 12-race series.

At Sears Point, George Follmer, Elliott Forbes-Robinson, Greg Pickett, Gene Felton and others did their best to stop Hobbs, but his DeAtley/Budweiser Camaro was once again victorious.

In the only ’83 race Hobbs hasn’t won, at Moroso, he was passed by Felton on the last lap and finished second.

Felton took the Bondo/Oftedahl Trans Am to a second-place finish at Sears Point. He dropped to 10th place from his seventh starting position but strongly worked his way to the front, taking Tom Gloy for second on the 38th of 40 laps.

Gloy, in his Lane Sports Mercury Capri, hung on to take third, after running second much of the race.

Elliott Forbes-Robinson, making what may be his only start of the season, brought his Huffaker Engineering Trans Am home fourth. Vern Smith took his best Trans-Am finish ever by coming from 18th qualifying spot to take fifth in his Trans-Lese Mercury Capri.

Steve Saleen came home sixth one lap down in his Pontiac Trans Am after starting 14th. Willy T. Ribbs ran as high as third, ahead of Felton, but suffered tire problems, including a puncture, and finished seventh in his DeAtley/Budweiser Camaro. Frank Emmett was eighth in his Supercuts Corvette, Les Lindley was ninth in his Camaro.

On Track

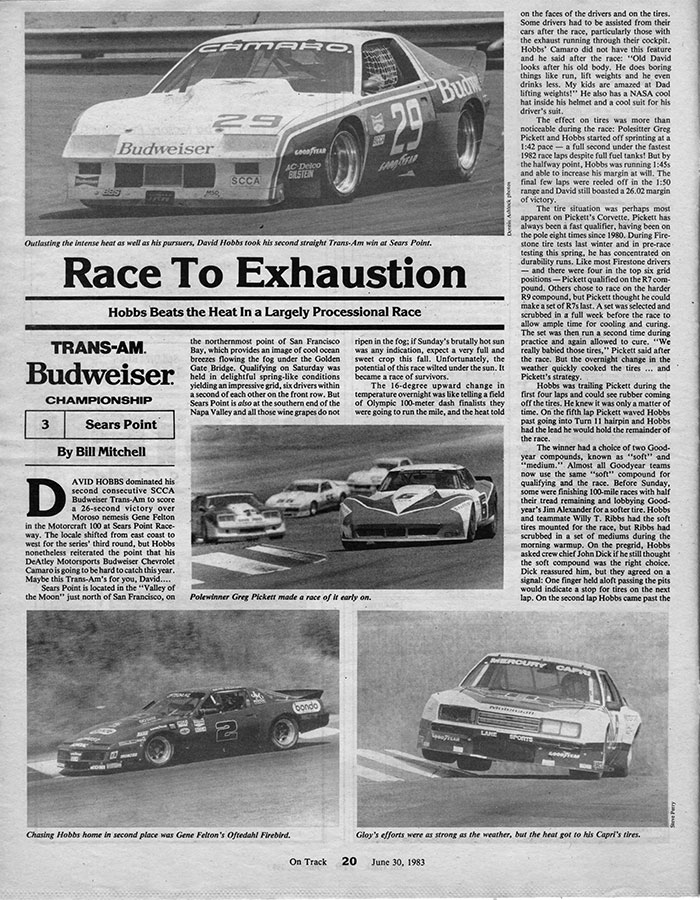

Race to Exhaustion

Hobbs Beats the Heat in a Largely Processional Race

TRANS-AM BUDWEISER

CHAMPIONSHIP

Sears Point

June 30, 1983

By Bill Mitchell

David Hobbs dominated his second consecutive SCCA Budweiser Trans-Am to score a 16-second victory over Moroso nemesis Gene Felton in the Motorcraft 100 at Sears Point Raceway. The locale shifted from east coast to west for the series’ third round, but Hobbs nonetheless reiterated the point that his DeAtley Motorsports Budweiser Chevrolet Camaro is going to be hard to catch this year. Maybe this Trans-Am’s for you, David….

Sears Point is located in the “Valley of the Moon” just north of San Francisco, on the northernmost point of San Francisco Bay, which provides an image of cool ocean breezes flowing the fog under the Golden Gate Bridge. Qualifying on Saturday was held in delightful spring-like conditions yielding an impressive grid, six drivers withing a second of each other on the front row. But Sears Point is also at the southern end of the Napa Valley and all those wine grapes do not ripen in the fog. If Sunday’s brutally hot sun was any indication, expect a very full and sweet crop this fall. Unfortunately, the potential of this race wilted under the sun. It became a race of survivors.

The 16-degree upward change in temperature overnight was like telling a field of Olympic 100-meter dash finalists they were going to run the mile, and the heat told on the faces of the drivers and on the tires. Some drivers had to be assisted from their cars after the race, particularly those with the exhaust running through their cockpit. Hobbs’ Camaro did not have this feature and he said after the race: “Old David looks after his old body. He does boring things like run, lift weights and he even drinks less. My kids are amazed at Dad lifting weights!” He also has a NASA cool hat inside his helmet and a cool suit for his driver’s suit.

The effect on tires was more than noticeable during the race: Polesitter Greg Pickett and Hobbs started off sprinting at a 1:42 pace – a full second under the fastest 1982 race laps despite full fuel tanks! But by the halfway point, Hobbs was running 1:45’s and able to increase his margin at will. The final few laps were reeled off in the 1:50 range and David still boasted a 26.02 margin of victory.

The tire situation was perhaps most apparent on Pickett’s Corvette. Pickett has always been a fast qualifier, having been on the pole eight times since 1980. During Firestone tire tests last winter and in pre-race testing this spring, he has concentrated on durability runs. Like most Firestone drivers – and there were four in the top six grid positions – Pickett qualified on the R7 compound. Others chose to race on the harder R9 compound, but Pickett thought he could make a set of R7s last. A set was selected and scrubbed in a full week before the race to allow ample time for cooling and curing. The set was then run a second time during practice and again allowed to cure. “We really babied those tires,” Pickett said after the race. But the overnight change in the weather quickly cooked the tires… and Pickett’s strategy.

Hobbs was trailing Pickett during the first four laps and could see rubber coming off the tires. He knew it was only a matter of time. On the fifth lap Pickett waved Hobbs past going into Turn 11 hairpin and Hobbs had the lead he would hold the remainder of the race.

The winner had a choice of two Goodyear compounds, known as “soft” and “medium.” Almost all Goodyear teams now use the same “soft” compound for qualifying and the race. Before Sunday, some were finishing 100-mile races with half their tread remaining and lobbying Goodyear’s Jim Alexander for a softer tire. Hobbs and teammate Willy T. Ribbs had the soft tires mounted for the race, but Ribbs had scrubbed in a set of mediums during the morning warmup. On the pregrid, Hobbs asked crew chief John Dick if he still thought the soft compound was the right choice. Dick reassured him, but they agreed on a signal: One finger held aloft passing the pits would indicate a stop for tires on the next lap….

Trans-Am Race Reports

Contemporary Articles Tell the Tale

Follow the DeAtley/Budweiser Motorsports Camaro team over the course of the 1983 Championship chase in the words of the competition press of the day.

In that journey, with all its ups and downs, you'll see a lot more ups than downs.

They truly earned the respect of their rivals as they reveal in these stories.

"To read the dozen 1983 SCCA Budweiser Trans-Am race reports is to see abundantly clear that most of them say the same thing. True, the words are slightly different, but the underlying theme is domination … a rout by the DeAtley Motorsports Chevrolet Camaros as driven by David Hobbs and Willy T. Ribbs."

"Veteran Hobbs and rookie Ribbs finished 1-2 in the drivers’ championship as the Budweiser-sponsored team won 10 of the 12 races (with the assistance of John Paul Jr. at Trois Rivieres) and set any number of other statistical records."

"No other drivers led even one lap of the last six races and Hobbs himself was not passed on the race track between the opener at Moroso ... and the Caesar’s Palace finale where the Englishman was cruising for championship-clinching points."

"A total of 36 Trans-Am teams appeared for the opening race at Moroso Motorsports Park, the largest single class opening field in the 18-year history of the series."

"The team best prepared for the opener at Moroso and the second race at Summit Point in West Virginia was DeAtley Motorsports. Their pair of Budweiser Chevrolet Camaros, driven by David Hobbs and Willy T. Ribbs, were exactly what the team’s plan called for. And the results reflected their achievement..."

"DeAtley Motorsports was perhaps the first to make the full commitment. They ordered three Chevrolet Camaro chassis from Speedway Engineering in southern California. Motors and rebuilds would be supplied by Dennis Fischer."

"The plan was to use proven and reliable parts (the phrase “cheap and available” is not the preferred nomenclature), and test exhaustively. From the results at Moroso and Summit Point, everyone began to wonder why he hadn’t thought of it first! How many race teams have ever filled the front row of the grid in only their second race?"

"The styles of David Hobbs and Willy T. Ribbs reflect their experience and background: Hobbs has two decades of experience in a vast variety of equipment and uncountable hours on the track. Ribbs has been very fast – he had the pole of the Long Beach Atlantic race in 1982 – but has had very little track time."

"Hobbs called the Summit Point race the best of his career from a traffic standpoint: 'I never had to lift.'”

"Ribbs also had the fastest lap in both races. The DeAtley team has their handling dialed in to the point where they can run the softest Goodyear compound the entire race distance."

"Lady Luck bestowed her good graces on David Hobbs at the Escort Radar Warning Budweiser Trans-Am at Summit Point."

"...arriving early was John Dick’s Budweiser/DeAtley crew with mounts for Hobbs and Ribbs. Both the Lane and DeAtley teams used the few days before Wednesday’s open practice to ready the cars. The level of that preparation was readily apparent..."

"Hobbs and Ribbs, however, continued running well, with Hobbs setting the fastest unofficial time of 1:16.0, and Ribbs second at 1:16.4."

RACE RESULTS

Hobbs wins Summit Point.

(Click on Report to Enlarge)

"The question is now, “WHO can stop David Hobbs?” Hobbs took his second SCCA Budweiser Trans-Am Championship victory in a row by cruising to victory in the Motorcraft 100 at Sears Point International Raceway on June 5."

"The Englishman thus has a commanding 20-point lead in the chase for the 1983 Budweiser Trans-Am Championship going into the June 12 G.I. Joe’s Rose Cup, the fourth round of the 12-race series."

"David Hobbs dominated his second consecutive SCCA Budweiser Trans-Am to score a 16-second victory over Moroso nemesis Gene Felton in the Motorcraft 100 at Sears Point Raceway."

"...Hobbs nonetheless reiterated the point that his DeAtley Motorsports Budweiser Chevrolet Camaro is going to be hard to catch this year. Maybe this Trans-Am’s for you, David…."

"...by the halfway point, Hobbs was running 1:45’s and able to increase his margin at will. The final few laps were reeled off in the 1:50 range and David still boasted a 26.02 margin of victory."

Hobbs wins Sears Point

(Click on Report to Enlarge)

Ribbs wins Portland

(Click on Report to Enlarge)

"Willy T. Ribbs won his second Trans-Am race of the year, finishing a comfortable 12.39 seconds ahead of his Budweiser/DeAtley Camaro teammate David Hobbs. It was the first 1-2 finish of the year for the team that has been all but completely dominant this season, but it was surprising to watch the ease with which they controlled the race."

"Ribbs took advantage of the clear track ahead of him and didn’t wait to see who would emerge in second place. On lap eight, he set the fastest race lap at 1:35.110 – faster than last year’s pole winning qualifying time!"

Ribbs wins Mid-Ohio

(Click on Report to Enlarge)

"Willy T. Ribbs made it two out of the last three on July 17 as he raced to victory in the Sports Car Club of America’s Budweiser Trans-Am Championship at the Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course."

"For Ribbs, it was his second win in the last month in the series. He scored his first ever Trans-Am triumph at Portland on June 12."

“'Everything went perfectly with the car,' said Ribbs, who set the fastest race lap and fastest average race speed records in the 100.8-mile event."

"Neil DeAtley’s Budweiser-backed racing team could easily be accused of having a rose-colored view of the Trans-Am world."

"David Hobbs edged closer to the SCCA’s 1983 Budweiser Trans-Am Championship by scoring a dominant victory at Elkhart Lake’s Road America. The veteran Britisher made it look easy, leading from green to checker and recording fastest race lap after qualifying on the pole."

"...the DeAtley duo put on quite an exhibition, taking nearly four seconds off the course record for Trans-Am cars, Hobbs leaving it at 2:17.233 with his teammate just over seven-tenths behind."

"The dominance of the DeAtley machines is seemingly easily explained by crew chief John Dick, who relates that, 'It’s all very elemental. You take simple cars, good engines and good drivers and go racing.'”

Hobbs wins Road America

(Click on Report to Enlarge)

"Englishman David Hobbs tightened his grip on the points lead in the 1983 Budweiser Trans-Am Championship Sunday as he rolled to his third Trans-Am victory of the season before 50,000 road racing fans at Road America on July 29."

"It marked the fifth victory of the season for the DeAtley Budweiser Camaros and pushed Hobbs’ lead in the points to a 106-88 margin over Tom Gloy, who finished third."

"Hobbs smashed the Trans-Am qualifying record during Friday’s TRW Fast Five qualifying session when he turned a 2:17.233, 104.931mph lap. That topped the record of 2:32.001, 102.129mph..."

"A near record Trans-Am field of 55 cars (59 is the record, set in 1966 at Sebring) took the green flag and Hobbs immediately jumped ahead with teammate Willy T. Ribbs right behind."

"Ribbs eventually carried the day, beating teammate Hobbs by 1.8 seconds. The average speed for the race was 100.719 miles per hour."

"Hobbs initially started driving for the DeAtley team on a bit of a whim. 'I hadn’t heard of them,' Hobbs said. 'But a friend rang me and said DeAtley was a bonafide guy and was very anxious for me to drive for him.'”

“The DeAtley cars are the absolute cream of the crop – good equipment and well sorted out. There’s nothing very magical about them. It’s a bit like the old Penske days – DeAtley doesn’t spend a fortune but he spends what it takes to win.”

Ribbs wins Brainerd

(Click on Report to Enlarge)

"John Paul Jr. made his first-ever Budweiser Trans-Am Championship appearance one to remember Sunday as he cruised to victory in the Trans-Am portion of the Labatt’s Grand Prix de Trois Rivieres on Sept. 5."

"Paul continued to build on his lead throughout the race and was never seriously pushed."

“'The car went really good all day,' said Paul of his victory."

"Willy T. Ribbs won the fourth Budweiser Trans-Am of his rookie season at Sears Point. The win from the front row moves Ribbs ahead of teammate David Hobbs in the win column, four to three..."

"It’s getting harder and harder to remember Ribbs is still a rookie with fewer than 30 races in his entire career."

"The DeAtley Motorsports team of Budweiser Camaros won their eighth race in 10 starts, took their fourth consecutive pole and led every lap for the fourth consecutive race."

"Hobbs has not been passed on the race track since the opener at Moroso..."

"David Hobbs came back to the Trans-Am with a vengeance. The June race at Sears Point had seen a remarkably tight grid with eight cars qualified within 1.4 seconds. Hobbs destroyed any thoughts of a repeat when he turned a 1:39.824, nearly a full second quicker than the June pole."

Ribbs wins Sears Point

(Click on Report to Enlarge)

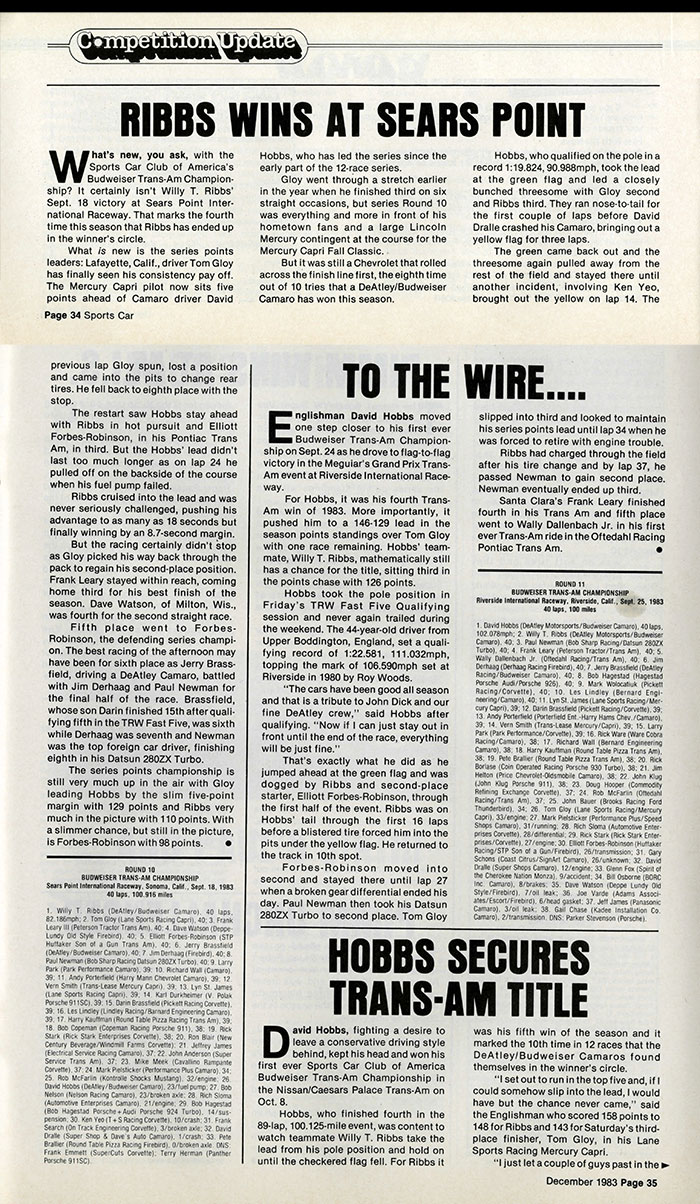

"What’s new, you ask, with the Sports Car Club of America’s Budweiser Trans-Am Championship? It certainly isn’t Willy T. Ribbs’ Sept. 18 victory at Sears Point International Raceway. That marks the fourth time this season that Ribbs has ended up in the winner’s circle."

"But it was still a Chevrolet that rolled across the finish line first, the eighth time out of 10 tries that a DeAtley/Budweiser Camaro has won this season."

"Ribbs cruised into the lead and was never seriously challenged, pushing his advantage to as many as 18 seconds but finally winning by an 8.7 second margin."

"Englishman David Hobbs moved one step closer to his first ever Budweiser Trans-Am Championship on Sept. 21 as he drove to flag-to-flag victory in the Megular’s Grand Prix Trans-Am event at Riverside International Raceway."

"For Hobbs, it was his fourth Trans-Am win of 1983. More importantly, it pushed him to a 146-129 lead in the season points standing..."

"Hobbs took the pole position in Friday’s TRW Fast Five Qualifying session and never again trailed during the weekend. The 44-year-old driver from Upper Boddington, England, set a qualifying record of 1:22.581, 111.032mph, topping the mark of 106.590mph set at Riverside in 1980 by Roy Woods."

“'The cars have been good all season and that is a tribute to John Dick and our fine DeAtley crew,' said Hobbs after qualifying. 'Now if I can just stay out in front until the end of the race, everything will be just fine.'”

"David Hobbs moved back atop the Budweiser Trans-Am championship with a flag-to-flag win at Riverside. Hobbs’ fourth victory in his DeAtley Motorsports Chevrolet Camaro gives him 146 points to 129 for Tom Gloy and 126 for Budweiser teammate Willy T. Ribbs, and means that a top 10 finish in the final race at Las Vegas will win the championship for Hobbs."

"Ribbs scored an impressive second-place finish in spite of a pit stop to change a blistered tire. The rookie – who also has four Trans-Am wins – now has a good chance of taking second in the series."

"Back on the track Willy T. was carving his way through the field and finally passed Paul Newman for second in the closing stages."

Hobbs wins Riverside

(Click on Report to Enlarge)

Ribbs wins Caesars Palace

Hobbs wins Trans-Am Championship

(Click on Report to Enlarge)

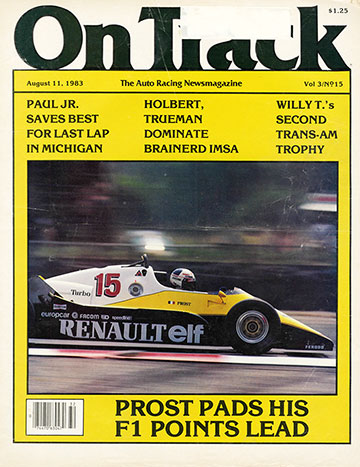

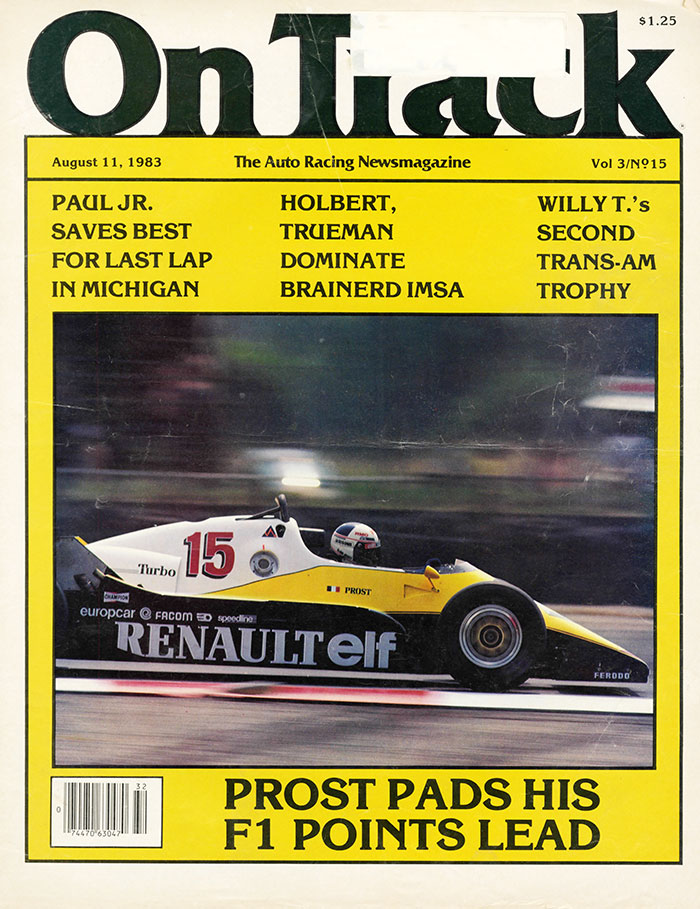

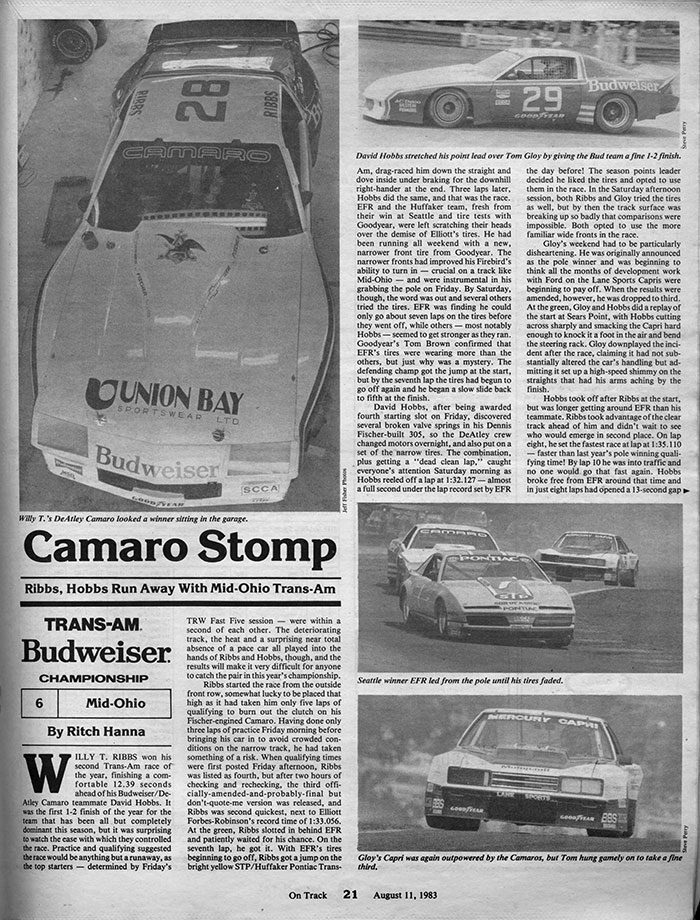

On Track

Camaro Stomp

Ribbs, Hobbs Run Away With Mid-Ohio Trans-Am

TRANS-AM BUDWEISER

CHAMPIONSHIP

Mid-Ohio

August 11, 1983

By Ritch Hanna

Willy T. Ribbs won his second Trans-Am race of the year, finishing a comfortable 12.39 seconds ahead of his Budweiser/DeAtley Camaro teammate David Hobbs. It was the first 1-2 finish of the year for the team that has been all but completely dominant this season, but it was surprising to watch the ease with which they controlled the race. Practice and qualifying suggested the race would be anything but a runaway, as the top starters – determined by Friday’s TRW Fast Five Session – were within a second of each other. The deteriorating track, the heat and a surprisingly near total absence of a pace car all played into the hands of Ribbs and Hobbs, though, and the results will make it difficult for anyone to catch the pair in this year’s championship.

Ribbs started the race from the outside front row, somewhat lucky to be placed that high as it had taken him only five laps of qualifying to burn out the clutch on his Fischer-engined Camaro. Having done only three laps of practice Friday morning before bringing his car in to avoid crowded conditions on the narrow track, he had taken something of a risk. When qualifying times were first posted Friday afternoon, Ribbs was listed as fourth, but after two hours of checking and rechecking, the third officially-amended-and-probably-final but don’t-quote-me version was released, and Ribbs was second quickest, next to Elliott Forbes-Robinson’s record time of 1:33.056. At the green, Ribbs slotted in behind EFR and patiently waited for his chance. On the seventh lap, he got it. With EFR’s tires beginning to go off, Ribbs got a jump on the bright yellow STP/Huffaker Pontiac Trans Am, drag-raced him down the straight and dove inside under braking for the downhill right-hander at the end. Three laps later, Hobbs did the same, and that was the race. EFR and the Huffaker team, fresh from their win at Seattle and tire tests with Goodyear, were left scratching their heads over the demise of Elliot’s tires. He had been running all weekend with a new, narrower front tire from Goodyear. The narrower fronts had improved his Firebird’s ability to turn in – crucial on a track like Mid-Ohio – and were instrumental in his grabbing the pole on Friday. By Saturday, though, the word was out and several others tried the tires. EFR was finding he could only go about seven laps on the tires before they went off, while others – most notably Hobbs – seemed to get stronger as they ran. Goodyear’s Tom Brown confirmed that EFR’s tires were wearing more than the others, but just why was a mystery. The defending champ got the jump at the start, but by the seventh lap the tires had begun to go off again and he began a slow slide back to fifth at the finish.

David Hobbs, after being awarded fourth starting slot on Friday, discovered several broken valve springs in his Dennis Fischer-build 305, so the DeAtley crew changed motors overnight, and also put on a set of the narrow tires. The combination, plus getting a “dead clean lap,” caught everyone’s attention Saturday morning as Hobbs reeled off a lap at 1:32.127 – almost a full second under the lap record set by EFR the day before! The season points leader decided he liked the tires and opted to use them in the race. In the Saturday afternoon session, both Ribbs and Gloy tried the tires as well, but by then the track surface was breaking up so badly that comparisons were impossible. Both opted to use the more familiar wide fronts in the race.

Gloy’s weekend had to be particularly disheartening. He was originally announced as the pole winner and was beginning to think all the months of development work with Ford on the Lane Sports Capris were beginning to pay off. When the results were amended, however, he was dropped to third. At the green, Gloy and Hobbs did a replay of the start at Sears Point, with Hobbs cutting across sharply and smacking the Capri hard enough to knock it a foot in the air and bend the steering rack. Gloy downplayed the incident after the race, claiming it had not substantially altered the car’s handling but admitting it set up a high-speed shimmy on the straights that had his arms aching by the finish.

Hobbs took off after Ribbs at the start, but was longer getting around EFR than his teammate. Ribbs took advantage of the clear track ahead of him and didn’t wait to see who would emerge in second place. On lap eight, he set the fastest race lap at 1:35.110 – faster than last year’s pole winning qualifying time! By lap 10 he was into traffic and no one would go that fast again. Hobbs broke free from EFR around that time and in just eight laps had opened a 13-second lap.

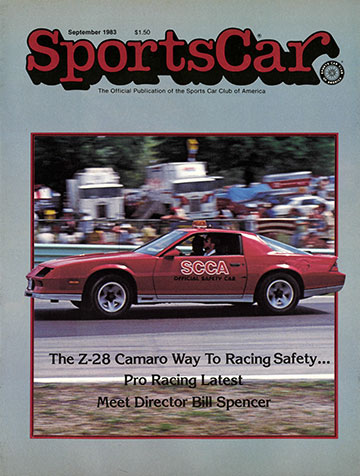

SportsCar

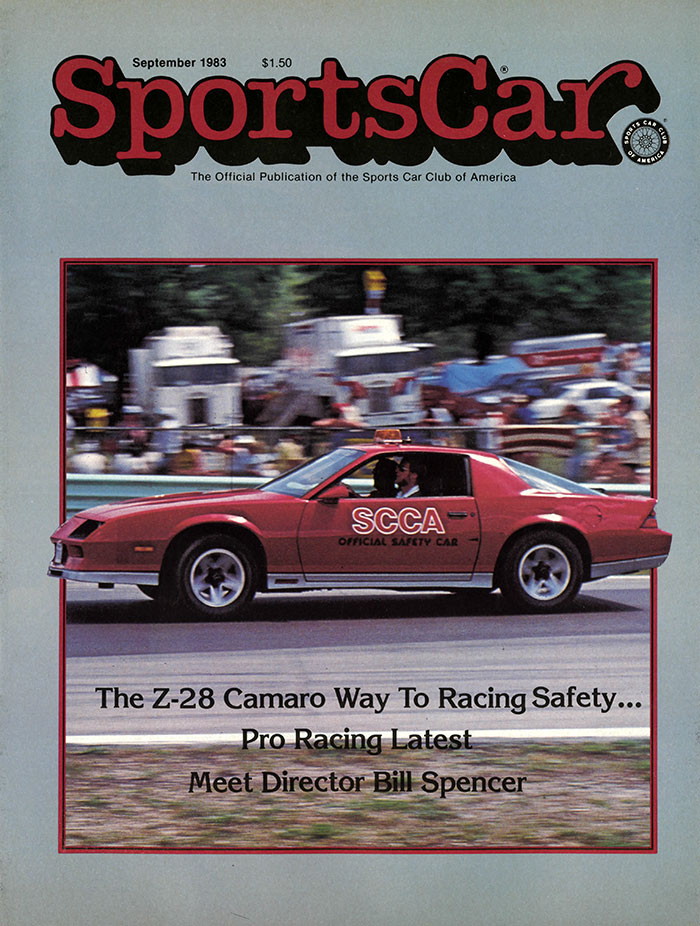

September 1983

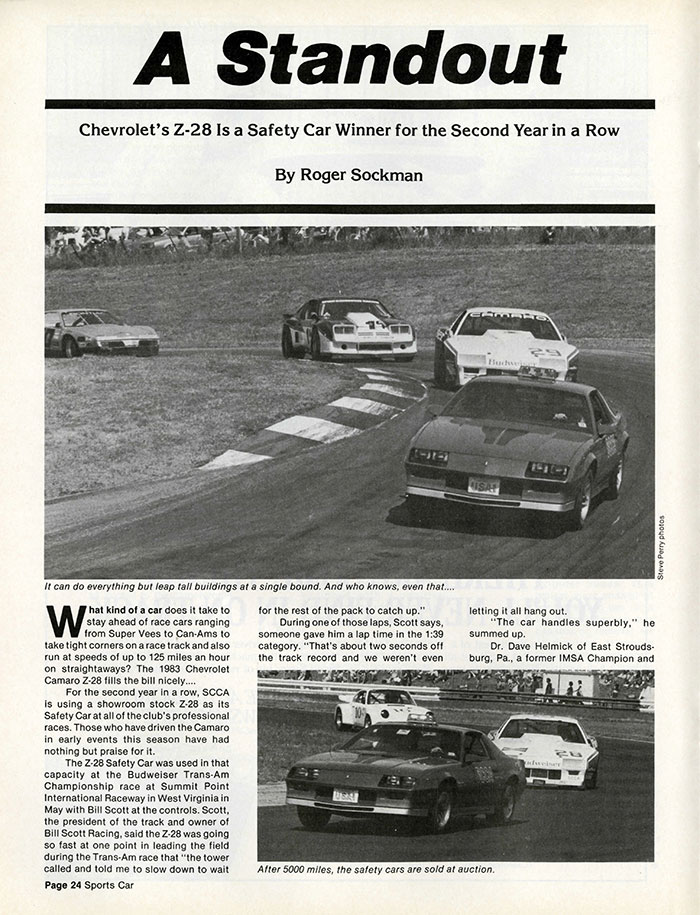

A Standout

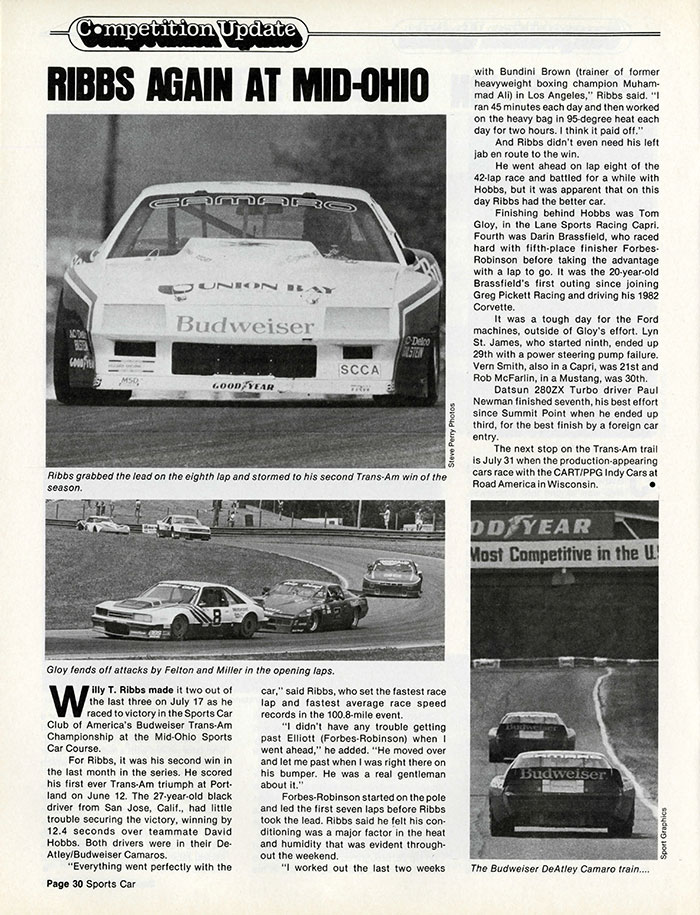

RIBBS AGAIN AT MID-OHIO

Willy T. Ribbs made it two out of the last three on July 17 as he raced to victory in the Sports Car Club of America’s Budweiser Trans-Am Championship at the Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course.

For Ribbs, it was his second win in the last month in the series. He scored his first ever Trans-Am triumph at Portland on June 12. The 27-year-old black driver from San Jose, Calif., had little trouble securing the victory, winning by 12.4 seconds over teammate David Hobbs. Both drivers were in their DeAtley/Budweiser Camaros.

“Everything went perfectly with the car,” said Ribbs, who set the fastest race lap and fastest average race speed records in the 100.8-mile event.

“I didn’t have any trouble getting past Elliott (Forbes-Robinson) when I went ahead,” he added. “He moved over and let me past when I was right there on his bumper. He was a real gentleman about it.”

Forbes-Robinson started on the pole and led the first seven laps before Ribbs took the lead. Ribbs said he felt his conditioning was a major factor in the heat and humidity that was evident throughout the weekend.

“I worked out the last two weeks with Bundini Brown (trainer of former heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali) in Los Angeles,” Ribbs said. “I ran 45 minutes each day and then worked on the heavy bag in 95-degree heat each day for two hours. I think it paid off.”

And Ribbs didn’t even need his left jab en route to the win.

He went ahead on lap eight of the 42-lap race and battled for a while with Hobbs, but it was apparent that on this day Ribbs had the better car.

Finishing behind Hobbs was Tom Gloy, in the Lane Sports Racing Capri. Fourth was Darin Brassfield, who raced hard with fifth-place finisher Forbes-Robinson before taking the advantage with a lap to go. It was the 20-year-old Brassfield’s first outing since joining Greg Pickett Racing and driving his 1982 Corvette.

It was a tough day for the Ford machines, outside of Gloy’s effort. Lyn St. James, who started ninth, ended up 29th with a power steering pump failure. Vern Smith, also in a Capri, was 21st and Rob McFarlin, in a Mustang, was 30th.

Datsun 280ZX Turbo driver Paul Newman finished seventh, his best effort since Summit Point when he ended up third, for the best finish by a foreign car entry.

The next stop on the Trans-Am trail is July 31 when the production-appearing cars race with the CART/PPG Indy Cars at Road America in Wisconsin.

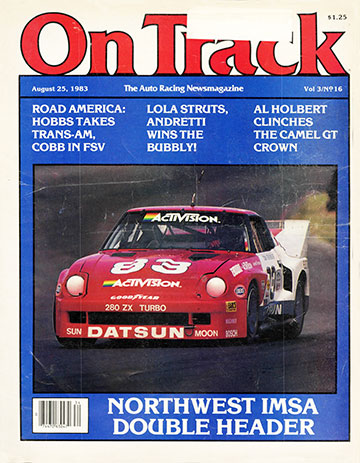

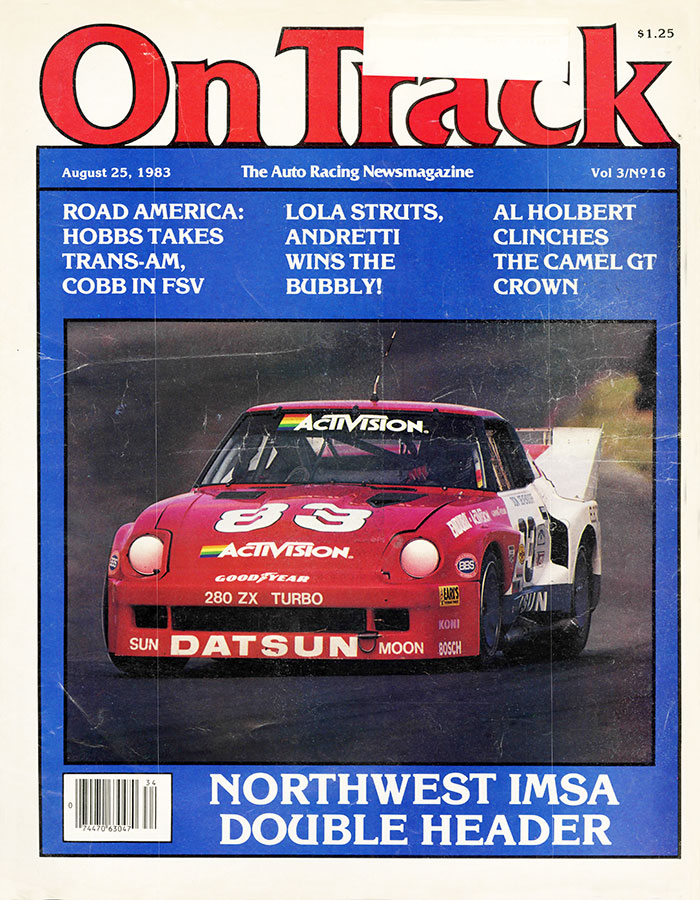

On Track

Applied Experience

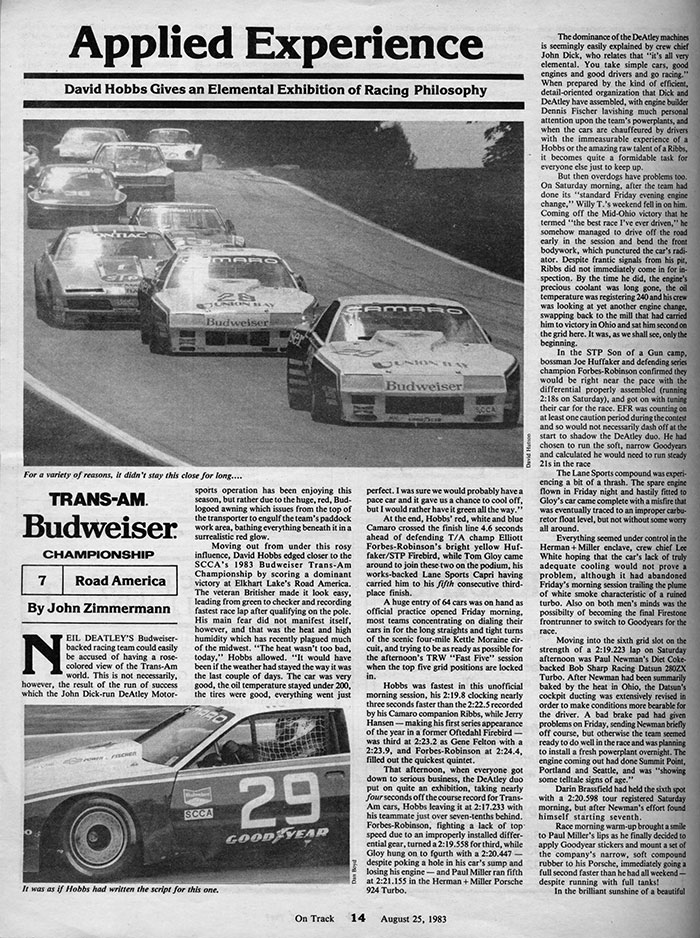

David Hobbs Gives an Elemental Exhibition of Racing Philosophy

TRANS-AM BUDWEISER CHAMPIONSHIP

Road America

August 25, 1983

By John Zimmerman

Neil DeAtley’s Budweiser-backed racing team could easily be accused of having a rose-colored view of the Trans-Am world. This is not necessarily, however, the result of the run of success with the John Dick-run DeAtley Motorsports operation has been enjoying this season, but rather due to the huge, red, Bud-logoed awning which issues from the top of the transporter to engulf the team’s paddock work area, bathing everything beneath it in a surrealistic red glow.

Moving out from under this rosy influence, David Hobbs edged closer to the SCCA’s 1983 Budweiser Trans-Am Championship by scoring a dominant victory at Elkhart Lake’s Road America. The veteran Britisher made it look easy, leading from green to checker and recording fastest race lap after qualifying on the pole. His main fear did not manifest itself, however, and that was the heat and high humidity which has recently plagued much of the Midwest. “The heat wasn’t too bad, today,” Hobbs allowed. “It would have been if the weather had stayed the way it was the last couple of days. The car was very good, the oil temperature stayed under 200, the tires were good, everything went just perfect. I was sure we would probably have a pace car and it gave us a chance to cool off, but I would rather have it green all the way.”

At the end, Hobbs’ red, white and blue Camaro crossed the finish line 4.6 seconds ahead of defending T/A champ Elliott Forbes-Robinson’s bright yellow Huffaker/STP Firebird, while Tom Gloy came around to join these two on the podium, his works-backed Lane Sports Capri having carried him to his fifth consecutive third-place finish.

A huge entry of 64 cars was on hand as official practice opened Friday morning, most teams concentrating on dialing their cars in for the long straights and tight turns of the scenic four-mile Kettle Moraine circuit, and trying to be as ready as possible for the afternoon’s TRW “Fast Five” session when the top five grid positions are locked in.

Hobbs was fastest in this unofficial morning session, his 2:19.8 clocking nearly three seconds faster than the 2:22.5 recorded by his Camaro companion Ribbs, while Jerry Hansen – making his first series appearance of the year in a former Oftedahl Firebird – was third at 2:23.2 as Gene Felton with a 2:23.9, and Forbes-Robinson at 2:24.4, filled out the quickest quintet.

That afternoon, when everyone got down to serious business, the DeAtley duo put on quite an exhibition, taking nearly four seconds off the course record for Trans-Am cars, Hobbs leaving it at 2:17.233 with his teammate just over seven-tenths behind. Forbes-Robinson, fighting a lack of top speed due to an improperly installed differential gear, turned a 219.558 for third, while Gloy hung on to fourth with a 2:20.447 – despite poking a hole in his car’s sump and losing his engine – and Paul Miller ran fifth at 221.155 in the Herman + Miller Porsche.

The dominance of the DeAtley machines is seemingly easily explained by crew chief John Dick, who relates that “it’s all very elemental. You take simple cars, good engines and good drivers and go racing.” When prepared by the kind of efficient, detail-oriented organization that Dick and DeAtley have assembled, with engine builder Dennis Fischer lavishing much personal attention upon the team’s powerplants, and when the cars are chauffeured by drivers with the immeasurable experience of a Hobbs or the amazing raw talent of a Ribbs, it becomes quite a formidable task for everyone else just to keep up.

But then overdogs have problems too. On Saturday morning, after the team had done its “standard Friday evening engine change,” Willy T.’s weekend fell in on him. Coming off the Mid-Ohio victory that he termed “the best race I’ve ever driven,” he somehow managed to drive off the road early in the session and bend the front bodywork, which punctured the car’s radiator. Despite frantic signals from his pit, Ribbs did not immediately come in for inspection. By the time he did, the engine’s precious coolant was long gone, the oil temperature was registering 240 and his crew was looking at another engine change, swapping back to the mill that had carried him to victory in Ohio and sat him second on the grid here. It was, as we shall see, only the beginning.

In the STP Son of a Gun camp, bossman Joe Huffaker and defending series champion Forbes-Robinson confirmed they would be right near the pace with the differential properly assembled (running 2:18s on Saturday), and got on with tuning their car for the race. EFR was counting on at least one caution period during the contest and so would not necessarily dash off at the start to shadow the DeAtley duo. He had chosen to run the soft, narrow Goodyears and calculated he would need to run steady 21s in the race.

The Lane Sports compound was experiencing a bit of a thrash. The spare engine flown in Friday night and hastily fitted to Gloy’s car came complete with a misfire that was eventually traced to an improper carburetor float level, but not without some worry all around.

Everything seemed under control in the Herman + Miller enclave, crew chief Lee White hoping that the car’s lack of truly adequate cooling would not prove a problem, although it had abandoned Friday’s morning session trailing the plume of white smoke characteristic of a ruined turbo. Also on both men’s minds was the possibility of becoming the final Firestone frontrunner to switch to Goodyears for the race.

Moving into the sixth grid slot on the strength of a 2:19.223 lap on Saturday afternoon was Paul Newman’s Diet Coke-backed Bob Sharp Racing Datsun 280ZX Turbo. After Newman had been summarily baked by the heat in Ohio, the Datsun’s cockpit ducting was extensively revised in order to make conditions more bearable for the driver. A bad brake pad had given problems on Friday, sending Newman briefly off course, but otherwise the team seemed ready to do well in the race and was planning to install a fresh powerplant overnight. The engine coming out had done Summit Point, Portland and Seattle, and was “showing some telltale signs of age.”

Darin Brassfield had held the sixth spot with a 2:20.598 tour registered Saturday morning, but after Newman’s effort found himself starting seventh.

Race morning warm-up brought a smile to Paul Miller’s lips as he finally decided to apply Goodyear stickers and mount a set of the company’s narrow, soft compound rubber to his Porsche, immediately going a full second faster than he had all weekend – despite running with full tanks.

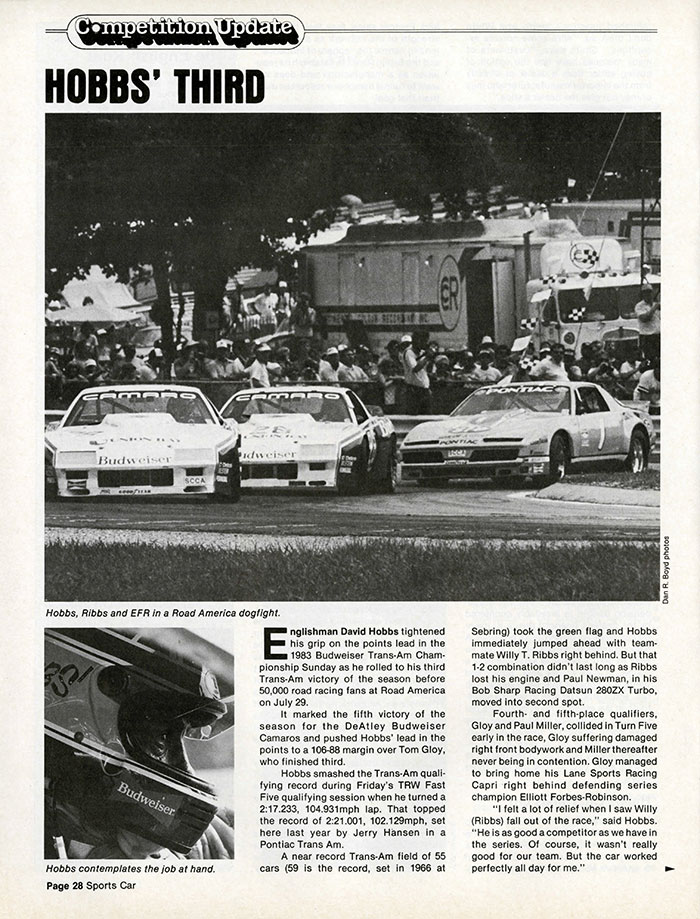

HOBBS’ THIRD

Englishman David Hobbs tightened his grip on the points lead in the 1983 Budweiser Trans-Am Championship Sunday as he rolled to his third Trans-Am victory of the season before 50,000 road racing fans at Road America on July 29.

It marked the fifth victory of the season for the DeAtley Budweiser Camaros and pushed Hobbs’ lead in the points to a 106-88 margin over Tom Gloy, who finished third.

Hobbs smashed the Trans-Am qualifying record during Friday’s TRW Fast Five qualifying session when he turned a 2:17.233, 104.931mph lap. That topped the record of 2:32.001, 102.129mph, set here last year by Jerry Hansen in a Pontiac Trans Am.

A near record Trans-Am field of 55 cars (59 is the record, set in 1966 at Sebring) took the green flag and Hobbs immediately jumped ahead with teammate Willy T. Ribbs right behind. But that 1-2 combination didn’t last long as Ribbs lost his engine and Paul Newman, in his Bob Sharp Racing Datsun 280ZX Turbo, moved into second spot.

Fourth-and-fifth-place qualifiers, Gloy and Paul Miller, collided in Turn Five early in the race, Gloy suffering damaged right front bodywork and Miller thereafter never being in contention. Gloy managed to bring home his Lane Sports Racing Capri right behind defending series champion Elliott Forbes-Robinson.

“I felt a lot of relief when I saw Willy (Ribbs) fall out of the race,” said Hobbs. “He is as good a competitor as we have in the series. Of course, it wasn’t really good for our team. But the car worked perfectly all day for me.”

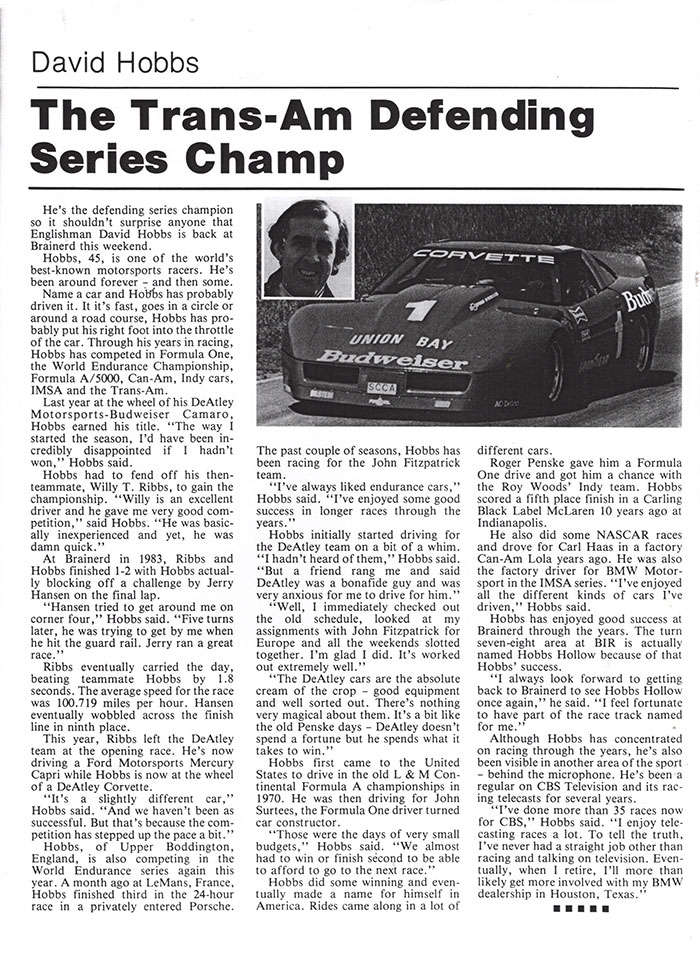

David Hobbs

The Trans-Am Defending Series Champ

He’s the defending series champion so it shouldn’t surprise anyone that Englishman David Hobbs is back at Brainerd this weekend.

Hobbs, 45, is one of the world’s best-known motorsports racers. He’s been around forever – and then some.

Name a car and Hobbs has probably put his right foot into the throttle of the car. Through his years in racing, Hobbs has competed in Formula One, the World Endurance Championship, Formula A/5000, Can-Am, Indy cars, IMSA and the Trans-Am.

Last year at the wheel of his DeAtley Motorsports-Budweiser Camaro, Hobbs earned his title. “The way I started the season, I’d have been incredibly disappointed if I hadn’t won,” Hobbs said.

Hobbs had to fend off his then-teammate, Willy T. Ribbs, to gain the championship. “Willy is an excellent driver and he gave me very good competition,” said Hobbs. “He was basically inexperienced and yet, he was damn quick.”

At Brainerd in 1983, Ribbs and Hobbs finished 1-2 with Hobbs actually blocking off a challenge by Jerry Hansen on the final lap.

“Hansen tried to get around me on corner four,” Hobbs said. “Five turns later, he was trying to get by me when he hit the guard rail. Jerry ran a great race.”

Ribbs eventually carried the day, beating teammate Hobbs by 1.8 seconds. The average speed for the race was 100.719 miles per hour. Hansen eventually wobbled across the finish line in ninth place.

This year, Ribbs left the DeAtley team at the opening race. He’s now driving a Ford Motorsports Mercury Capri while Hobbs is now at the wheel of a DeAtley Corvette.

“It’s a slightly different car,” Hobbs said. “And we haven’t been as successful. But that’s because the competition has stepped up the pace a bit.”

Hobbs, of Upper Boddington, England, is also competing in the World Endurance series again this year. A month ago at LeMans, France, Hobbs finished third in the 24-hour race in a privately entered Porsche. The past couple of seasons, Hobbs has been racing for the John Fitzpatrick team.

“I’ve always liked endurance cars,” Hobbs said. “I’ve enjoyed some good success in longer races through the years.”

Hobbs initially started driving for the DeAtley team on a bit of a whim. “I hadn’t heard of them,” Hobbs said. “But a friend rang me and said DeAtley was a bonafide guy and was very anxious for me to drive for him.”

“Well, I immediately checked out the old schedule, looked at my assignments with John Fitzpatrick for Europe and all the weekends slotted together. I’m glad I did. It’s worked out extremely well.”

“The DeAtley cars are the absolute cream of the crop – good equipment and well sorted out. There’s nothing very magical about them. It’s a bit like the old Penske days – DeAtley doesn’t spend a fortune but he spends what it takes to win.”

Hobbs first came to the United States to drive in the old L & M Continental Formula A championships in 1970. He was then driving for John Surtees, the Formula One driver turned car constructor.

“Those were the days of very small budgets,” Hobbs said. “We almost had to win or finish second to be able to afford to go to the next race.”

Hobbs did some winning and eventually made a name for himself in America. Rides came along in a lot of different cars.

Roger Penske gave him a Formula One drive and got him a chance with the Roy Woods’ Indy team. Hobbs scored a fifth place finish in a Carling Black Label McLaren 10 years ago at Indianapolis.

He also did some NASCAR races and drove for Carl Haas in a factory Can-Am Lola years ago. He was also the factory driver for BMW Motorsport in the IMSA series. “I’ve enjoyed all the different kinds of cars I’ve driven,” Hobbs said.

Hobbs has enjoyed good success at Brainerd through the years. The turn seven-eight area at BIR is actually named Hobbs Hollow because of that Hobbs’ success.

“I always look forward to getting back to Brainerd to see Hobbs Hollow once again,” he said. “I feel fortunate to have part of the track named for me.”

Although Hobbs has concentrated on racing through the years, he’s also been visible in another area of the sport – behind the microphone. He’s been a regular on CBS Television and its racing telecasts for several years.

“I’ve done more than 35 races now for CBS,” Hobbs said. “I enjoy telecasting races a lot. To tell the truth, I’ve never had a straight job other than racing and talking on television. Eventually, when I retire, I’ll more than likely get more involved with my BMW dealership in Houston, Texas.”

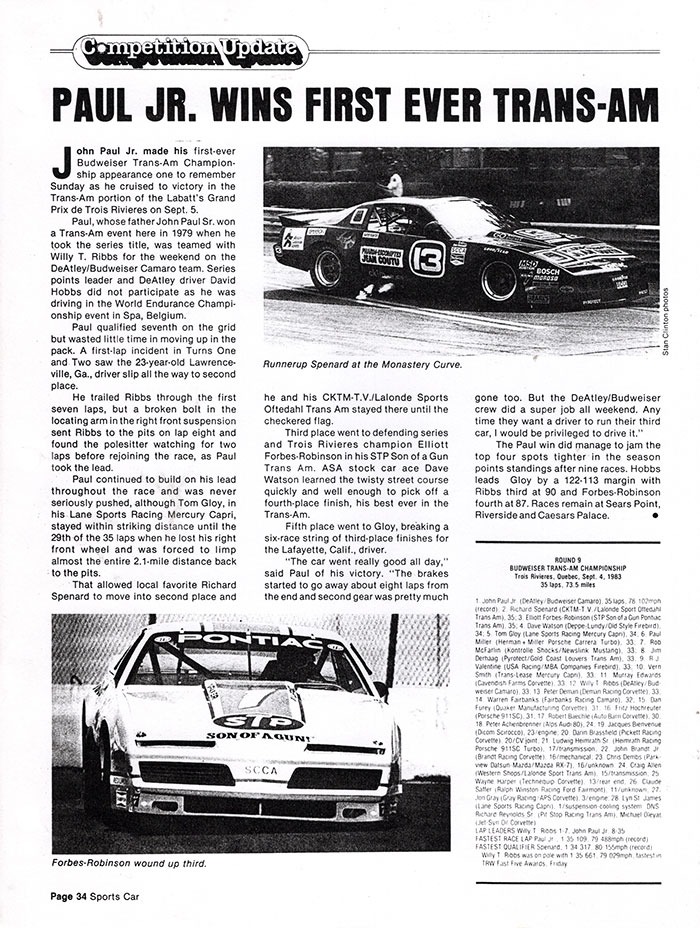

Competition Update

Paul Jr. Wins First Ever Trans-Am

John Paul Jr. made his first-ever Budweiser Trans-Am Championship appearance one to remember Sunday as he cruised to victory in the Trans-Am portion of the Labatt’s Grand Prix de Trois Rivieres on Sept. 5.

Paul, whose father John Paul Sr. won a Trans-Am event here in 1979 when he took the series title, was teamed with Willy T. Ribbs for the weekend on the DeAtley/Budweiser Camaro team. Series points leader and DeAtley driver David Hobbs did not participate as he was driving in the World Endurance Championship event in Spa, Belgium.

Paul qualified seventh on the grid but wasted little time in moving up in the pack. A first-lap incident in Turns One and Two saw the 23-year-old Lawrenceville, Ga. Driver slip all the way to second place.

He trailed Ribbs through the first seven laps, but a broken bolt in the locating arm in the right front suspension sent Ribbs to the pits on lap eight and found the polesitter watching for two laps before rejoining the race, as Paul took the lead.

Paul continued to build on his lead throughout the race and was never seriously pushed, although Tom Gloy, in his Lane Sports Racing Mercury Capri, stayed within striking distance until the 29th of the 35 laps when he lost his right front wheel and was forced to limp almost the entire 2.1-mile distance back to the pits.

That allowed local favorite Richard Spenard to move into second place and he and his CKTM-T.V./Lalonde Sports Oftedahl Trans Am stayed there until the checkered flag.

Third place went to defending series and Trois Rivieres champion Elliott Forbes-Robinson in his STP Son of a Gun Trans Am. ASA stock car ace Dave Watson learned the twisty street course quickly and well enough to pick off a fourth-place finish, his best ever in the Trans-Am.

Fifth place went to Gloy, breaking a six-race string of third-place finishes for the Lafayette, Calif., driver.

“The car went really good all day,” said Paul of his victory. “The brakes started to go away about eight laps from the end and second gear was pretty much gone too. But the DeAtley/Budweiser crew did a super job all weekend. Any time they want a driver to run their third car, I would be privileged to drive it.”

The Paul win did manage to jam the top four spots tighter in the season points standings after nine races. Hobbs leads Gloy by a 122-113 margin with Ribbs third at 90 and Forbes-Robinson fourth at 87. Races remain at Sears Point, Riverside and Caesars Palace.

On Track

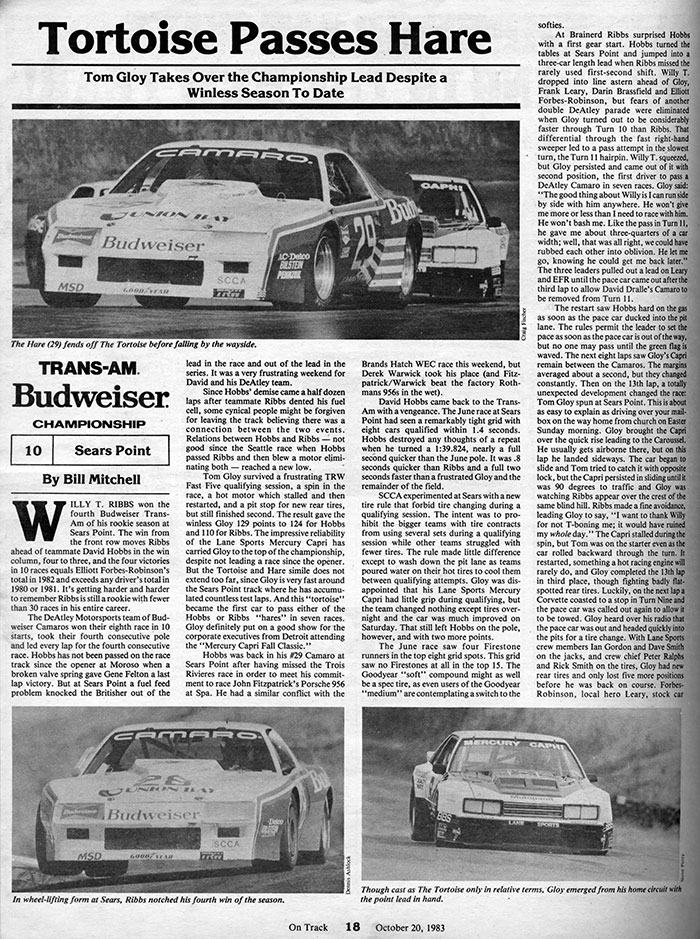

Tortoise Passes Hare

Tom Gloy Takes Over the Championship Lead Despite a Winless Season To Date

TRANS-AM BUDWEISER CHAMPIONSHIP

Sears Point

October 20

By Bill Mitchell

Willy T. Ribbs won the fourth Budweiser Trans-Am of his rookie season at Sears Point. The win from the front row moves Ribbs ahead of teammate David Hobbs in the win column, four to three, and the four victories in 10 races equals Elliott Forbes-Robinson’s total in 1982 and exceeds any driver’s total in 1980 or 1981. It’s getting harder and harder to remember Ribbs is still a rookie with fewer than 30 races in his entire career.

The DeAtley Motorsports team of Budweiser Camaros won their eighth race in 10 starts, took their fourth consecutive pole and led every lap for the fourth consecutive race. Hobbs has not been passed on the race track since the opener at Moroso when a broken valve spring gave Gene Felton a last lap victory. But at Sears Point a fuel feed problem knocked the Britisher out of the lead in the series. It was a very frustrating weekend for David and his DeAtley team.

Since Hobbs’ demise came a half dozen laps after teammate Ribbs dented his fuel cell, some cynical people might be forgiven for leaving the track believing there was a connection between the two events. Relations between Hobbs and Ribbs – not good since the Seattle race when Hobbs passed Ribbs and then blew a motor eliminating both – reached a new low.

Tom Gloy survived a frustrating TRW Fast Five qualifying session, a spin in the race, a hot motor which stalled and then restarted, and a pit stop for new rear tires, but still finished second. The result gave the winless Gloy 129 points to 124 for Hobbs and 110 for Ribbs. The impressive reliability of the Lane Sports Mercury Capri has carried Gloy to the top of the championship, despite not leading a race since the opener. But the Tortoise and Hare simile does not extend too far, since Gloy is very fast around the Sears Point track where he has accumulated countless test laps. And this “tortoise” became the first car to pass either of the Hobbs or Ribbs “hares” in seven races. Gloy definitely put on a good show for the corporate executives from Detroit attending the “Mercury Capri Fall Classic.”

Hobbs was back in his #29 Camaro at Sears Point after having missed the Trois Rivieres race in order to meet his commitment to race John Fitzpatrick’s Porsche 956 at Spa. He had a similar conflict with the Brands Hatch WEC race this weekend, but Derek Warwick took his place (and Fitzpatrick/Warwick beat the Rothmans 956s in the wet).

David Hobbs came back to the Trans-Am with a vengeance. The June race at Sears Point had seen a remarkably tight grid with eight cars qualified within 1.4 seconds. Hobbs destroyed any thoughts of a repeat when he turned a 1:39.824, nearly a full second quicker than the June pole. It was .8 seconds quicker than Ribbs and a full two seconds faster than a frustrated Gloy and the remainder of the field.

SCCA experimented at Sears with a new rule that forbid tire changing during a qualifying session. The intent was to prohibit the bigger teams with tire contracts from using several sets during a qualifying session while other teams struggled with fewer tires. The rule made little difference except to wash down the pit lane as teams poured water on their hot tires to cool them between qualifying attempts. Gloy was disappointed that his Lane Sports Mercury Capri had little grip during qualifying, but the team changed nothing except tires overnight and the car was much improved on Saturday. That still left Hobbs on the pole, however, and with two more points.

The June race saw four Firestone runners in the top eight grid spots. This grid saw no Firestones at all in the top 15. The Goodyear “soft” compound might as well be a spec tire, as even users of the Goodyear “medium” are contemplating a switch to the softies.

At Brainerd Ribbs surprised Hobbs with a first gear start. Hobbs turned the tables at Sears Point and jumped into a three-car length lead when Ribbs missed the rarely used first-second shift. Willy T. dropped into line astern ahead of Gloy, Fank Leary, Darin Brassfield and Elliot Forbes-Robinson, but fears of another double DeAtley parade were eliminated when Gloy turned out to be considerably faster through Turn 10 than Ribbs. That differential through the fast right-hand sweeper led to a pass attempt in the slowest turn, the Turn 11 hairpin. Willy T. squeezed, but Gloy persisted and came out of it with second position, the first driver to pass a DeAtley Camaro in seven races. Gloy said: “The good thing about Willy is I can run side by side with him anywhere. He won’t give me more or less than I need to race with him. He won’t bash me. Like the pass in Turn 11, he gave me about three-quarters of a car width; well, that was all right, we could have rubbed each other into oblivion. He let me go, knowing he could get me back later.” The three leaders pulled out a lead on Leary and EFR until the pace car came out after the third lap to allow David Dralle’s Camaro to be removed from Turn 11.