1983 BUDWEISER TRANS-AM

The Other Season

By Bill Mitchell

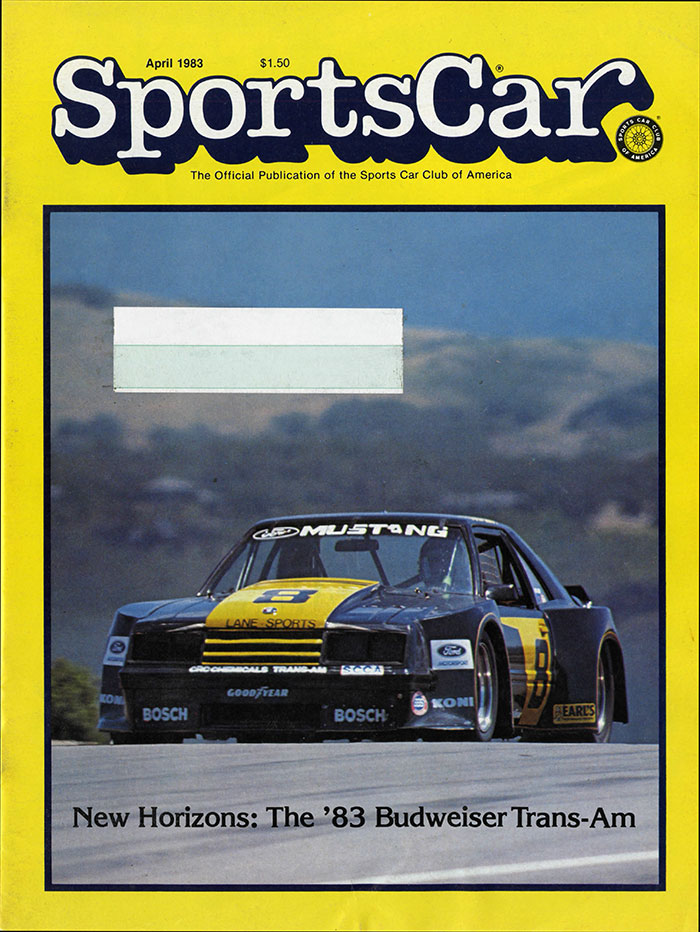

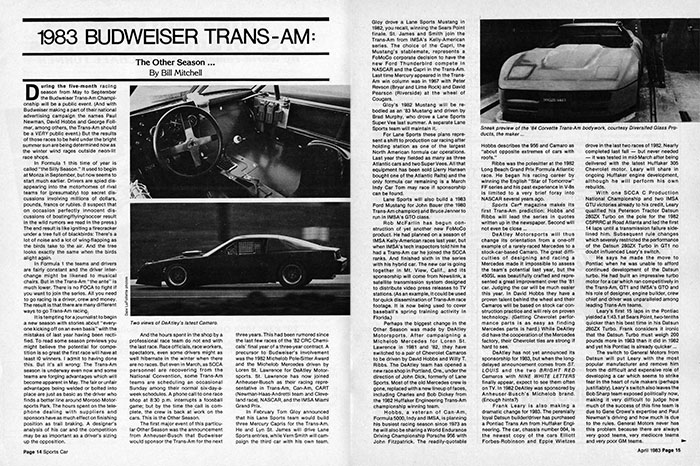

During the five-month racing season from May to September the Budweiser Trans-Am Championship will be a public event. (And with Budweiser making a part of their national advertising campaign the names Paul Newman, David Hobbs, and George Follmer, among others, the Trans-Am should be a VERY public event.) But the results of those races to be held under the bright summer sun are being determined now as the winter wind rages outside neon-lit race shops.

In Formula 1 this time of year is called “the Silly Season.” It used to begin at Monza in September, but now seems to start much earlier. Drivers are spied disappearing into the motorhomes of rival teams for (presumably) top secret discussions involving millions of dollars, pounds, francs or rubles. (I suspect that on occasion perfectly innocent discussions of boating/flying/soccer result in the wild rumors we read in the press.) The end result is like igniting a firecracker under a tree full of blackbirds: There’s a lot of noise and a lot of wing-flapping as the birds take to the air. And the tree looks exactly the same when the birds alight again.

In Formula 1 the teams and drivers are fairly constant and the driver interchange might be likened to musical chairs. But in the Trans-Am “the ante” is much lower. There is no FOCA to fight if you want to join the series. All you need to go racing is a driver, crew and money. The result is that there are many different ways to go Trans-Am racing.

It is tempting for a journalist to begin a new season with stories about “everyone kicking off on an even basis” with the mistakes of last year having been rectified. To read some season previews you might believe the potential for competition is so great the first race will have at least 10 winners. I admit to having done this. But it’s all wrong: The Trans-Am season is underway even now and some teams are forging advantages which will become apparent in May. The fair or unfair advantages being welded or bolted into place are just as basic as the driver who finds a better line around Moroso Motorsports Park. The hours spent on the telephone dealing with suppliers and sponsors have as much effect on finishing position as trail braking. A designer’s analysis of his car and the competition may be as important as a driver’s sizing up the opposition.

And the hours spent in the shop by a professional race team do not end with the last race. Race officials, race workers, spectators, even some drivers might as well hibernate in the winter when there are no races. But even in March, as SCCA personnel are recovering from the National Convention, some Trans-Am teams are scheduling an occasional Sunday among their normal six-day-a-week schedules. A phone call to one race shop at 8:30 p.m. interrupts a foosball game; but by the time the call is complete, the crew is back at work on the cars. This is the Other Season.

The first major event of this particular Other Season was the announcement from Anheuser-Busch that Budweiser would sponsor the Trans-Am for the next three years. This had been rumored since the last few races of the ’82 CRC Chemicals’ final year of a three-year contract. A precursor to Budweiser’s involvement was the 1982 Michelob Mercedes driven by Loren St. Lawrence for DeAtley Motorsports. St. Lawrence has now joined Anheuser-Busch as their racing representative in Trans-Am, Can-Am, CART (Newman-Haas-Andretti team and Cleveland race), NASCAR, and the IMSA Miami Grand Prix.

In February Tom Gloy announced that his Lane Sports team would build three Mercury Capris for the Trans-Am. He and Lyn St. James will drive Lane Sports entries, while Vern Smith will campaign the third car with his own team.

Gloy drove a Lane Sports Mustang in 1982, you recall, winning the Sears Pont finale. St. James and Smith join the Trans-Am from IMSA’s Kelly-American series. The choice of the Capri, the Mustang’s stablemate, represents a FoMoCo corporate decision to have the new Ford Thunderbird compete in NASCAR and the Capri in the Trans-Am. Last time Mercury appeared in the Trans-Am win column was in 1967 with Peter Revson (Bryar and Lime Rock) and David Pearson (Riverside) at the wheel of Cougars.

Gloy’s 1982 Mustang will be rebodied as an ’83 Mustang and driven by Brad Murphy, who drove a Lane Sports Super Vee last summer. A separate Lane Sports team will maintain it.

For Lane Sports these plans represent a shift to production car racing after holding station as one of the largest North American formula car operations. Last year they fielded as many as three Atlantic cars and two Super Vees. All that equipment has been sold (Jerry Hansen bought one of the Atlantic Ralts) and the only formula car remaining is a March Indy Car Tom may race if sponsorship can be found.

Lane Sports will also build a 1983 Ford Mustang for John Bauer (the 1980 Trans-Am champion) and Bruce Jenner to run in IMSA’s GTO class.

Rob McFarlin has begun construction of yet another new FoMoCo product. He had planned on a season of IMSA Kelly-American races last year, but when IMSA’s tech inspectors told him he had a Trans-Am car he joined the SCCA ranks. And finished sixth in the series with his hybrid car. The new car is going together in Mt. View, Calif., and its sponsorship will come from Newslink, a satellite transmission system designed to distribute video press releases to TV stations. (As an example, it could be used for quick dissemination of Trans-Am race footage. It is now being used to cover baseball’s spring training activity in Florida.)

Perhaps the biggest change in the Other Season was made by DeAtley Motorsports. After campaigning a Michelob Mercedes for Loren St. Lawrence in 1981 and ’82, they have switched to a pair of Chevrolet Camaros to be driven by David Hobbs and Willy T. Ribbs. The DeAtley team has opened a new race shop in Portland, Ore., under the direction of John Dick, formerly of Lane Sports. Most of the old Mercedes crew is gone, replaced with a new lineup of faces, including Charles and Bob Dickey from the 1982 Huffaker Engineering Trans-Am championship winning team.

Hobbs, a veteran of Can-Am, Formula 5000, Indy and IMSA, is planning his busiest racing season since 1972 as he will also be sharing a World Endurance Driving Championship Porsche 956 with John Fitzpatrick. The readily-quotable Hobbs describes the 956 and Camaro as “about opposite extremes of cars with roofs.”

Ribbs was the polesitter at the 1982 Long Beach Grand Prix Formula Atlantic race. He began his racing career by winning the English “Star of Tomorrow” FF series and his past experience in V-8s is limited to a very brief foray into NASCAR several years ago.

Sports Car magazine makes its first Trans-Am prediction: Hobbs and Ribbs will lead the series in quotes written up in the newspaper. Second will not even be close.

DeAtley Motorsports will thus change its orientation from a one-off example of a rarely-raced Mercedes to a stock-car-based Camaro. The great difficulties in designing and racing a Mercedes made it impossible to assess the team’s potential last year, but the 450SL was beautifully crafted and represented a great improvement over the ’81 car. Judging the car will be much easier this year. In David Hobbs they have a proven talent behind the wheel and their Camaros will be based on stock car construction practice and will rely on proven technology. (Getting Chevrolet performance parts is as easy as finding Mercedes parts is hard.) While DeAtley did have the cooperation of the Mercedes factory, their Chevrolet ties are strong if hard to see.

DeAtley has not yet announced its sponsorship for 1983, but when the long-delayed announcement comes from ST. LOUIS and the two BRIGHT RED Camaros with NINE WHITE LETTERS finally appear, expect to see them often on TV. In 1982 DeAtley was sponsored by Anheuser-Busch’s Michelob brand. (Enough hints?)

Frank Leary is also making a dramatic change for 1983. The perennially loyal Datsun builder/driver has purchased a Pontiac Trans Am from Huffaker Engineering. The car, chassis number 004, is the newest copy of the cars Elliott Forbes-Robinson and Eppie Wietzes drove in the last two races of 1982. Nearly completed last fall – but never needed – it was tested in mid-March after being delivered with the latest Huffaker 305 Chevrolet motor. Leary will share in ongoing Huffaker engine development, although he will perform his own rebuilds.

With one SCCA C Production National Championship and two IMSA GTU victories already to his credit, Leary qualified his Peterson Tractor Datsun 280ZX Turbo on the pole for the 1982 CSPRRC at Road Atlanta and led the first 14 laps until a transmission failure sidelined him. Subsequent rule changes which severely restricted the performance of the Datsun 280ZX Turbo in GT1 no doubt influenced Leary’s switch.

He says he made the move to Pontiac when he was unable to afford continued development of the Datsun turbo. He had built an impressive turbo motor for a car which ran competitively in the Trans-am, GT1 and IMSA’s GTO and his role of designer, engine builder, crew chief and driver was unparalleled among leading Trans-Am teams.

Leary’s first 15 laps in the Pontiac yielded a 1:43.1 at Sears Point, two-tenths quicker than his best time in his Datsun 280ZX Turbo. Frank considers it ironic that the Datsun Turbo must weigh 200 pounds more in 1983 than it did in 1982 and yet his Pontiac is already quicker…

The switch to General Motors from Datsun will put Leary with the most popular manufacturer and remove him from the difficult and expensive role of developing a car which seems to strike fear in the heart of rule makers (perhaps justifiably). Leary’s switch also leaves the Bob Sharp team exposed politically now, making it very difficult to judge how much of the success of this fine team is due to Gene Crowe’s expertise and Paul Newman’s driving and how much is due to the rules. General Motors never has this problem because there are always very good teams, very mediocre teams and very poor GM teams.

The Porsche Carrera 924 Turbo will be many times more numerous than the Datsun Turbo. Doc Bundy, winner of two races in 1982, will be back in a new Holbert Racing car. And with engine development being done at McLaren and possibly elsewhere, the 2-liter four-banger may become a qualifying threat for the first time. Last year Bundy’s Dykstra-chassis was severely under-powered, even in comparison to other 924 teams. Their competitiveness was due to Bundy’s fine sense of pace and having a tested car early in the series.

The last time McLaren (Detroit) worked on a 2-liter, four-cylinder turbo, it was for David Hobbs’ BMW 320i. Hobbs finished fifth in the IMSA GT series, won at Elkhart Lake and BMW now has a four-cylinder turbo in Formula 1. If history repeats itself, expect Bundy to qualify in the top five and be a definite threat on race day.

Bundy’s old car was being sought by Paul Miller of Herman + Miller, but Bob Hagestad got there first with a check and the car is his.

Monte Shelton is building a new Porsche 911SC, which he says “will have all the trick parts known to man.” At the new 2000 lb. weight limit the 911SC might be the sleeper of 1983. And if that doesn’t work, Monte still has the 930 Turbo with which he won at Elkhart Lake in 1980 and 1981.

1982 Rookie of the Year Darin Brassfield will be in a 1984 Corvette designed by Lee Dykstra, powered by Ryan Falconer 304 V-8s, and built by a crew headed by Englishman John Bright.

Dykstra has been a very busy designer of late, having done the Holbert Racing Porsche, John Paul’s ultra-trick Porsche 935 and Bob Tullius’ Jaguar GTP car last year, in addition to several consulting projects. Crew chief John Bright is probably the fastest crew chief in the Trans-Am. As a former English Formula 3 driver and occasional co-driver on Ralph Cooke’s Lola GTP car, he can be expected to do some of the initial testing of the Corvette.

George Follmer is also building one of more 1984 Corvettes with ex-Lotus designer Martin Waide doing the pencil work. George will be one driver in the 1983 Trans-Am with ties to the “good old days.” He was Trans-Am champion in 1972 (Javelin) and 1976 (Porsche).

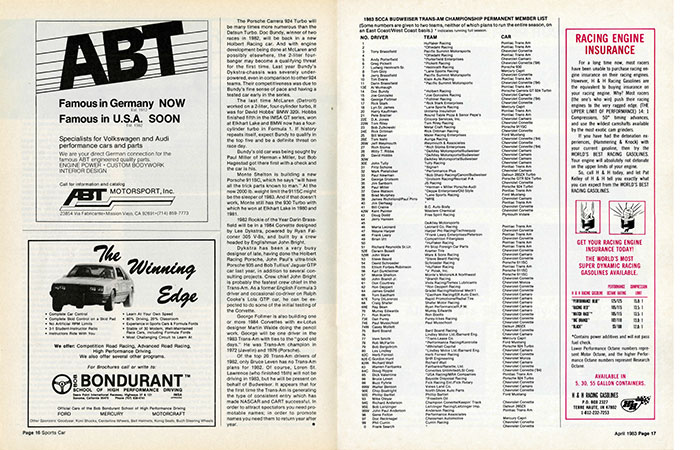

Of the top 20 Trans-Am drivers of 1982, only Bruce Leven has no Trans-Am plans for 1982. Of course, Loren St. Lawrence (who finished 15th) will not be driving in 1983, but he will be present on behalf of Budweiser. It appears that for the first time the Trans-Am is generating the type of consistent entry which has made NASCAR and CART successful. In order to attract spectators you need promotable names: in order to promote names you need them to return year after year.

Road and Track

RACING AT RANDOM

Where has the sport been?

Where is it going?

About the Sport

By Joe Rusz

It’s not quite time for “Auld Lang Syne,” so put the Moet et Chandon back into the refrigerator and stash the noisemakers and confetti. The year’s not over yet, although we are certainly on the downside of the 1983 racing season. Maybe you should break out the champagne after all, as I bring you up to date on some of the significant happenings in the world of motor racing.

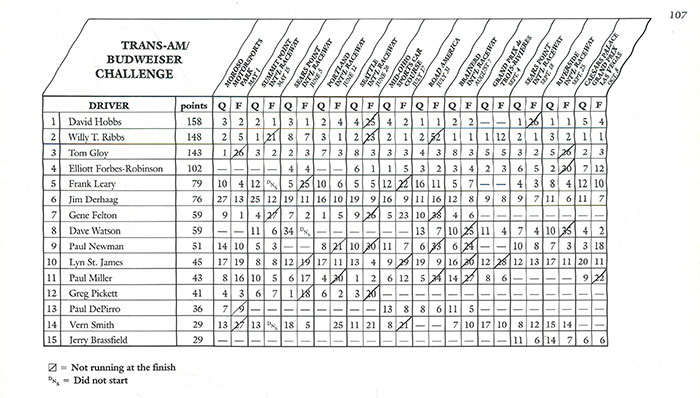

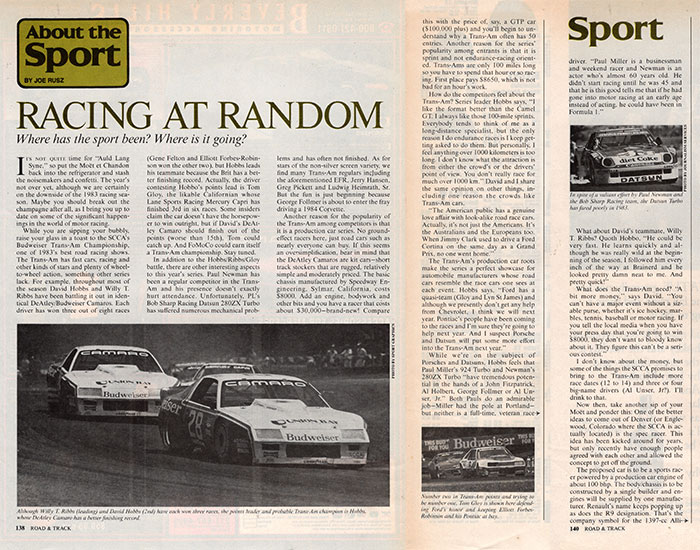

While you are sipping your bubbly, raise your glass in a toast to the SCCA’s Budweiser Trans-Am Championship, one of 1983’s best road racing shows. The Trans-Am has fast cars, racing and other kinds of stars and plenty of wheel-to-wheel action, something other series lack. For example, throughout most of the season David Hobbs and Willy T. Ribbs have been battling it out in identical DeAtley/Budweiser Camaros. Each driver has won three out of eight races (Gene Felton and Elliott Forbes-Robinson won the other two), but Hobbs leads his teammate because the Brit has a better finishing record. Actually, the driver contesting Hobbo’s points lead is Tom Gloy, the likable Californian whose Lane Sports Racing Mercury Capri has finished 3rd in six races. Some insiders claim the car doesn’t have the horsepower to win outright, but if David’s DeAtley Carmaro should finish out of the points (worse than 15th), Tom could catch up. And FoMoCo could earn itself a Trans-Am championship. Stay tuned.

In addition to the Hobbs/Ribbs/Gloy battle, there are other interesting aspects to this year’s series. Paul Newman has been a regular competitor in the Trans-Am and his presence doesn’t exactly hurt attendance. Unfortunately, PL’s Bob Sharp Racing Datsun 280ZX Turbo has suffered numerous mechanical problems and has often not finished. As for stars of the non-silver screen variety, we find many Trans-Am regulars including the aforementioned EFR, Jerry Hansen, Greg Pickett and Ludwig Heimrath, Sr. But the fun is just beginning because George Follmer is about to enter the fray driving a 1984 Corvette.

Another reason for the popularity of the Trans-Am among competitors is that it is a production car series. No ground-effect racers here, just road cars such as nearly everyone can buy. If this seems an oversimplification, bear in mind that the DeAtley Camaros are kit cars—short track stockers that are rugged, relatively simple and moderately priced. The basic chassis is manufactured by Speedway Engineering, Sylmar, California, costs $8000. Add an engine, bodywork and other bits and you have a racer that costs about $30,000—brand new! Compare this with the price of, say a GTP car ($100,000 plus) and you’ll begin to understand why a Trans-Am often has 50 entries.

Another reason for the series’ popularity among entrants is that it is sprint and not endurance-racing oriented. Trans-Ams are only 100 miles long so you have to spend that hour or so racing. First place pays $8650, which is not bad for an hour’s work.

How do the competitors feel about the Trans-Am? Series leader Hobbs says, “I like the format better than the Camel GT. I always like those 100-mile sprints. Everybody tends to think of me as a long-distance specialist, but the only reason I do endurance races is I keep getting asked to do them. But personally, I feel anything over 1000 kilometers is too long. I don’t know what the attraction is from either the crowd’s or the drivers’ point of view. You don’t really race for much over 1000 km.” David and I share the same opinion on other things, including one reason the crowds like Trans-Am cars.

“The American public has a genuine love affair with look-alike road race cars. Actually, it’s not just the Americans. It’s the Australians and the Europeans too. When Jimmy Clark used to drive a Ford Cortina on the same day as a Grand Prix, no one went home.”

The Trans-Am’s production car roots make the series a perfect showcase for automobile manufacturers whose road cars resemble the race cars one sees at each event. Hobbs says, “Ford has a quasi-team (Gloy and Lyn St. James) and although we presently don’t get any help from Chevrolet, I think we will next year. And I suspect Porsche and Datsun will put some more effort into the Trans-Am next year.

While we’re on the subject of Porsches and Datsuns, Hobbs feels that Paul Miller’s 924 Turbo and Newman’s 280ZX Turbo “have tremendous potential in the hands of a John Fitzpatrick, Al Hobert, George Follmer or Al Unser, Jr.” Both Pauls do an admirable job—Miller had the pole at Portland—but neither is a full-time veteran race driver. “Paul Miller is a businessman and weekend racer and Newman is an actor who’s almost 60 years old. He didn’t start racing until he was 45 and that he is this good tells me that if he had gone into motor racing at an early age instead of acting, he could have been in Formula 1.”

What about David’s teammate, Willy T. Ribbs? Quoth Hobbo, “He could be very fast. He learns quickly and although he was really wild at the beginning of the season, I followed him every inch of the way at Brainerd and he looked pretty dam neat to me. And pretty quick!”

What does the Trans-Am need? “A bit more money,” says David. “You can’t have a major event without a sizable purse, whether it’s ice hockey, marbles, tennis, baseball, or motor racing. If you tell the local media when you have your press day that you’re going to win $8000, they don’t want to bloody know about it. They figure this can’t be a serious contest.”

I don’t know about the money, but some of the things the SCCA promises to bring to the Trans-Am include more race dates (12 to 14) and three or four big-name drivers (Al Unser, Jr?).

I’ll drink to that.

Super Chevy Magazine

Trans-Am Champs

To win, it takes a Chevy!

By Joe Stephen

Businessman and sportsman, Neil DeAtley, had run an exotic Mercedes team in the Sports Car Club of America’s Budweiser Trans-Am Series for two years. John Dick had been crew chief on the factory-backed Mustang Trans-Am team for those same two years. Both had said they wanted to run something different and unusual. One day they both decided winning would be something different and unusual!

The two men joined forces and Dick told DeAtley, “If you want to win you’ve gotta run a Chevy.” DeAtley said, “Go for it.” Putting their heads together they came up with a trick but simple solution.

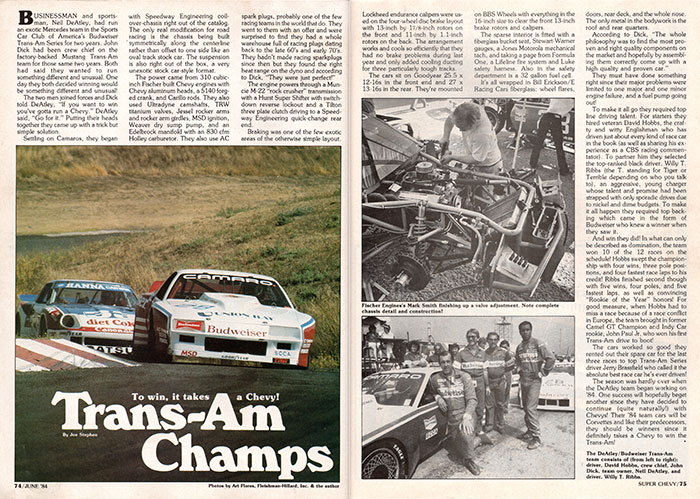

Settling on Camaros, they began with Speedway Engineering's coil-over-chassis right out of the catalog. The only real modification for road racing is the chassis being built symmetrically along the centerline rather than offset to one side like an oval track stock car. The suspension is also right out of the box, a very unexotic stock car-style format.

The power came from 310 cubic-inch Fischer built Chevy engines with Chevy aluminum heads, a 5140 forged crank, and Carillo rods. They also used Ultradyne camshafts, TRW titanium valves, Jessel rocker arms and rocker arm girdles, MSD ignition, Weaver dry sump pump, and an Edelbrock manifold with an 830 cfm Holley carburetor. They also use AC spark plugs, probably one of the few racing teams in the world that do. They went to them with an offer and were surprised to find they had a whole warehouse full of racing plugs dating back to the late 60’s and early 70’s. They hadn’t made racing sparkplugs since then but they found the right heat range on the dyno and according to Dick, “They were just perfect.”

The engine powers through a Muncie M-22 “rock crusher” transmission with a Hurst Super Shifter with switch-down reverse lockout and a Tilton three plate clutch driving to a Speedway Engineering quick-change rear end.

Braking was one of the few exotic areas of the otherwise simple layout. Lockheed endurance calipers were used on the four-wheel disc brake layout with 13-inch by 1 7/8 inch rotors on the front and 11-inch by 1.1-inch rotors on the back. The arrangement works and cools so efficiently that they had no brake problems during last year and only added cooling ducting for three particularly tough tracks.

The cars sit on Goodyear 25.5 x 12-16s in the front and 27 x 13-16s in the rear. They’re mounted on BBS Wheels with everything in the 16-inch size to clear the front 13-inch brake rotors and calipers.

The sparse interior is fitted with a fiberglass bucket seat, Stewart-Warner gauges, a Jones Motorola mechanical tach, and taking a page from Formula One, a Lifeline fire system and Luke safety harness. Also in the safety department is a 32-gallon fuel cell.

It’s all wrapped in Bill Erickson/E Racing Cars fiberglass: wheel flares, doors, rear deck, and the whole nose. The only metal in the bodywork is the roof and rear quarters.

According to Dick, “The whole philosophy was to find the most proven and right quality components on the market and hopefully by assembling them correctly come up with a high-quality and proven car.”

They must have done something right since their major problems were limited to one major and one minor engine failure, and a fuel pump going out!

To make it all go they required top line driving talent. For starters they hired veteran David Hobbs, the crafty and witty Englishman who has driven just about every kind of race car in the book (as well as sharing his experience as a CBS racing commentator). To partner him they selected the top-ranked black driver, Willy T. Ribbs (the T standing for Tiger or Terrible depending on who you talk to), an aggressive, young charger whose talent and promise had been strapped with only sporadic drives due to nickel and dime budgets. To make it all happen they required top backing which came in the form of Budweiser who knew a winner when they saw it.

And win they did! In what can only be described as domination, the team won 10 of the 12 races on the schedule! Hobbs swept the championship with four wins, three pole positions, and four fastest race laps to his credit! Ribbs finished second though with five wins, four poles, and five fastest laps, as well as convincing “Rookie of the Year” honors! For good measure, when Hobbs had to miss a race because of a race conflict in Europe, the team brought in former Camel GT Champion and Indy Car rookie, John Paul Jr., who won his first Trans-Am drive to boot!

The cars worked so good they rented out their spare car for the last three races to top Trans-Am Series driver Jerry Brassfield who called it the absolute best race car he’s ever driven!

The season was hardly over when the DeAtley team began working on ’84. One success will hopefully beget another since they have decided to continue (quite naturally) with Chevys! Their ’84 team cars will be Corvettes and like their predecessors, they should be winners since it definitely takes a Chevy to win the Trans-Am!

Press Clippings

Wherever the Trans-Am raced, the automotive press was fascinated as the DeAtley Motorsports Budweiser Camaros simply dominated.

These are some of their stories.

"The first major event of this particular Other Season was the announcement from Anheuser-Busch that Budweiser would sponsor the Trans-Am for the next three years."

"Perhaps the biggest change in the Other Season was made by DeAtley Motorsports. After campaigning a Michelob Mercedes for Loren St. Lawrence in 1981 and ’82, they have switched to a pair of Chevrolet Camaros to be driven by David Hobbs and Willy T. Ribbs. The DeAtley team has opened a new race shop in Portland, Ore., under the direction of John Dick, formerly of Lane Sports."

"Sports Car magazine makes its first Trans-Am prediction: Hobbs and Ribbs will lead the series in quotes written up in the newspaper. Second will not even be close."

"In David Hobbs they have a proven talent behind the wheel and their Camaros will be based on stock car construction practice and will rely on proven technology."

"The story of the 1983 SCCA Budweiser Trans-Am Championship has to begin with the DeAtley Motorsports Chevrolet Camaros driven by Series Champion David Hobbs and Rookie-of-the-Year Willy T. Ribbs."

"This new team burst on the scene and dominated the series in a manner unmatched since the days of Mark Donohue and the Penske Racing Camaros."

"Taking seven pole positions and winning ten of the twelve races, the team of Hobbs and Ribbs finished one-two in the Drivers’ Championship, winning the 'Manufacturer of the Year' award for Chevrolet."

"Indeed, the hallmark of the series became a pair of red and white Budweiser Camaros running nose-to-tail in the lead."

"The money and time saved on construction were spent on an exhaustive test and development program. The newest team was the first to have their new cars on the test track."

"Either Hobbs or Ribbs, alone, would have given DeAtley a good season. Both, together, led to domination, even if there were occasional headaches."

"A total of 415 cars started the 12 race series, an average of 34.6 per race. But the two cars that will be remembered in 1983 are the two that went the fastest and won the most – the red and white DeAtley Motorsports/Budweiser Racing Camaros of David Hobbs and Willy T. Ribbs."

"...raise your glass in a toast to the SCCA’s Budweiser Trans-Am Championship, one of 1983’s best road racing shows. The Trans-Am has fast cars, racing and other kinds of stars and plenty of wheel-to-wheel action, something other series lack."

"...throughout most of the season David Hobbs and Willy T. Ribbs have been battling it out in identical DeAtley/Budweiser Camaros. Each driver has won three out of eight races..."

"Another reason for the popularity of the Trans-Am among competitors is that it is a production car series. No ground-effect racers here, just road cars such as nearly everyone can buy. If this seems an oversimplification, bear in mind that the DeAtley Camaros are kit cars—short track stockers that are rugged, relatively simple and moderately priced."

"How do the competitors feel about the Trans-Am? Series leader Hobbs says, “I like the format better than the Camel GT. I always like those 100-mile sprints."

"Businessman and sportsman, Neil DeAtley, had run an exotic Mercedes team in the Sports Car Club of America’s Budweiser Trans-Am Series for two years. John Dick had been crew chief on the factory-backed Mustang Trans-Am team for those same two years. Both had said they wanted to run something different and unusual. One day they both decided winning would be something different and unusual!"

"The two men joined forces and Dick told DeAtley, 'If you want to win you’ve gotta run a Chevy.'"

"DeAtley said, 'Go for it.'"

"According to Dick, 'The whole philosophy was to find the most proven and right quality components on the market and hopefully by assembling them correctly come up with a high-quality and proven car.'

They must have done something right..."

"To make it all go they required top line driving talent. For starters they hired veteran David Hobbs, the crafty and witty Englishman who has driven just about every kind of race car in the book (as well as sharing his experience as a CBS racing commentator).

To partner him they selected the top-ranked black driver, Willy T. Ribbs (the T standing for Tiger or Terrible depending on who you talk to), an aggressive, young charger whose talent and promise had been strapped with only sporadic drives due to nickel and dime budgets.

To make it all happen they required top backing which came in the form of Budweiser who knew a winner when they saw it."

"...they rented out their spare car for the last three races to top Trans-Am Series driver Jerry Brassfield who called it the absolute best race car he’s ever driven!"

AutoRacing1983

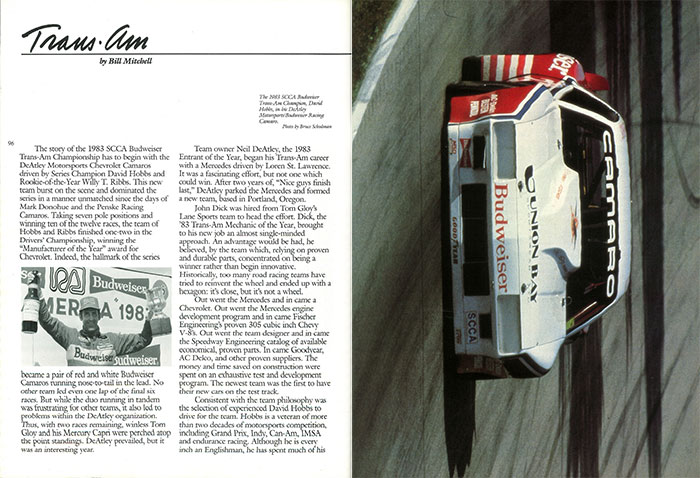

The story of the 1983 SCCA Budweiser Trans-Am Championship has to begin with the DeAtley Motorsports Chevrolet Camaros driven by Series Champion David Hobbs and Rookie-of-the-Year Willy T. Ribbs. This new team burst on the scene and dominated the series in a manner unmatched since the days of Mark Donohue and the Penske Racing Camaros. Taking seven pole positions and winning ten of the twelve races, the team of Hobbs and Ribbs finished one-two in the Drivers’ Championship, winning the “Manufacturer of the Year” award for Chevrolet. Indeed, the hallmark of the series became a pair of red and white Budweiser Camaros running nose-to-tail in the lead. No other team led even one lap of the final six races. But while the duo running in tandem was frustrating for other teams, it also led to problems within the DeAtley organization. Thus, with two races remaining, winless Tom Gloy and his Mercury Capri were perched atop the point standings. DeAtley prevailed, but it was an interesting year.

Team owner Neil DeAtley, the 1983 Entrant of the Year, began his Trans-Am career with a Mercedes driven by Loren St. Lawrence. It was a fascinating effort, but not one which could win. After two years of, “Nice guys finish last,” Deatley parked the Mercedes and formed a new team, based in Portland, Oregon.

John Dick was hired from Tom Gloy’s Lane Sports team to head the effort. Dick, the ’83 Trans-Am Mechanic of the Year, brought to his new job an almost single-minded approach. An advantage would be had, he believed, by the team which, relying on proven and durable parts, concentrated on being a winner rather than being innovative. Historically, too many road racing teams have tried to reinvent the wheel and ended up with a hexagon: it’s close, but it’s not a wheel. Out went the Mercedes and in came a Chevrolet.

Out went the Mercedes engine development program and in came Fischer Engineering’s proven 305 cubic inch Chevy V-8’s. Out went the team designer and in came the Speedway Engineering catalog of available economical, proven parts. In came Goodyear, AC Delco, and other proven suppliers. The money and time saved on construction were spent on an exhaustive test and development program. The newest team was the first to have their new cars on the test track.

Consistent with the team philosophy was the selection of experienced David Hobbs to drive for the team. Hobbs is a veteran of more than two decades of motorsports competition, including Grand Prix, Indy, Can-Am, IMSA and endurance racing. Although he is every inch an Englishman, he has spent much of his racing career in the United States. His dry wit and knowledge have also made him a well-regarded TV motorsports announcer.

But if Hobbs was consistent with the “tried and proven” philosophy, second driver Willy T. Ribbs was equally inconsistent. Untested and unproven, the highly promotable driver had barely two dozen races in his career. In 1977 he won the English “Star of Tomorrow” series for novice Formula Ford drivers. But “tomorrow” was a long time coming. Returning to the United States, he participated in some invitational testing sessions and got occasional rides, but nothing permanent. Indeed, in 1982, he won the pole for the Formula Atlantic race run in support of the Long Beach Grand Prix. Nonetheless, much of his time was spent working as a plumber for his father.

DeAtley planned to build three cars for his two drivers. Running two cars not only allowed the sharing of the team’s fixed costs, but improved the odds of sponsor Budweiser having at least one car running at the finish. Either Hobbs or Ribbs, alone, would have given DeAtley a good season. Both, together, led to domination, even if there were occasional headaches.

When the series opened at Moroso Motorsports Park in West Palm Beach, Florida, Tom Gloy was fastest right out of the truck. But his Mercury Capri had a limited supply of engines, forcing him to count his laps. The DeAtley Camaros relentlessly whittled away at his advantage by practicing lap after lap after lap. Gloy, Ribbs and Hobbs all led the race. But Gene Felton took the victory on the last lap as Hobbs was slowed by a broken valve spring.

The second race, at Summit Point, West Virginia, featured the DeAtley duo in high gear, qualifying one-two. In the race, they nearly lapped the entire field. Ribbs, however, was impatient and crashed while trying to lap third-place Greg Pickett. Hobbs, on the other hand, survived even a pit stop for a new tire, to take his first Trans-Am win.

The west coast swing saw Hobbs repeat at Sears Point, followed by Ribbs’ first American victory at the team’s home track in Portland. But race five, at Seattle, brought problems. Ribbs, leading Hobbs, was held up in traffic. Hobbs took over first place. Now following in his teammate’s wake, Ribbs felt Hobbs had violated the team rules – rules, he, Ribbs, had obeyed in earlier races. (Hobbs, when later apprised of Ribbs’ feeling, described his teammate as immature.) Neither driver’s attitude was improved when Hobbs blew a motor and Ribbs, following right behind, crashed on the resulting oil. One engine failure had eliminated both cars. The drivers were hardly speaking. And the season was only half over.

Ribbs won at Mid-Ohio with Hobbs second. The veteran Hobbs won over a 54 car field at Road America while Ribbs lost a motor. At Brainerd, it was again a Ribbs-Hobbs one-two.

Trois-Rivieres witnessed a slightly different DeAtley duo. Filling in for Hobbs, who was committed to co-drive a Porsche 956 at Spa, Belgium, was John Paul, Sr. Of IMSA and CART fame. During the race, Ribbs suffered a suspension failure, forcing a pit stop. But DeAtley’s heart barely missed a beat as Paul proceeded to put the back-up car in victory circle.

The tension on the DeAtley team reached new heights during the series’ second visit to Sears Point. Upon a restart following a caution period, Ribbs tapped Hobbs, denting his fuel cell. Hobbs coasted to a stop six laps later with fuel starvation, undoubtedly blaming his teammate for his demise. As Hobbs watched, Ribbs took the win. Of even greater impact to the spectating Hobbs, Gloy finished second and took the series’ points lead.

Nerves were taut at Riverside as the DeAtley team concentrated its efforts on Hobbs’ attempt to regain the points advantage. A special qualifying motor gave Hobbs the pole with a qualifying run of 111.832, the fastest ever for a Trans-Am automobile. During the race, Ribbs followed team orders, staying behind his teammate, even as he crossed the finish line. Thus, Hobbs scored his fourth victory of the year. Gloy unwillingly cooperated in easing the strain. On lap 33 of the 40 lap event, a blown developmental engine necessitated a permanent pit stop. The showdown moved on to Caesars Palace, in Las Vegas, and the season’s final race.

Amidst the neon and glitter of the Las Vega strip, the 1983 Budweiser Trans-Am season came to a close with Hobbs clinching the Championship. Ribbs, showing his new maturity as a driver, captured his fifth victory of the season and moved past Gloy to take the position of runner-up in the points battle.

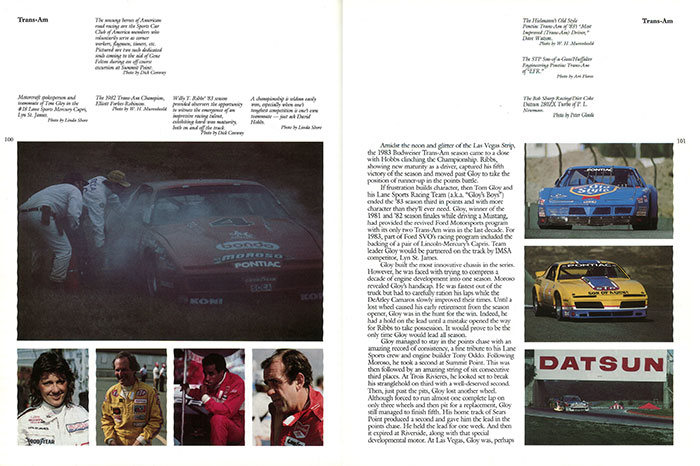

If frustration builds character, then Tom Gloy and his Lane Sports Racing Team (a.k.a. “Gloy’s Boys”) ended the ’83 season third in points and with more character than they’ll ever need. Gloy, winner of the 1981 and ’82 season finales while driving a Mustang, had provided the revived Ford Motorsports program with its only two Trans-Am wins in the last decade. For 1983, part of Ford SVO’s racing program included the backing of a pair of Lincoln-Mercury’s Capris. Team leader Gloy would be partnered on the track by IMSA competitor, Lyn St. James.

Gloy built the most innovative chassis in the series. However, he was faced with trying to compress a decade of engine development into one season. Moroso revealed Gloy’s handicap. He was fastest out of the truck but had to carefully ration his laps while the DeAtley Camaros slowly improved their times. Until a lost wheel caused his early retirement from the season opener, Gloy was in the hunt for the win. Indeed, he had a hold on the lead until a mistake opened the way for Ribbs to take possession. It would prove to be the only time that Gloy would lead all season.

Gloy managed to stay in the points chase with an amazing record of consistency, a fine tribute to his Lane Sports crew and engine builder Tony Oddo. Following Moroso, he took a second at Summit Point. This was then followed by an amazing string of six consecutive third places. At Trois Rivieres, he looked set to break his stranglehold on third with a well-deserved second. Then, just past the pits, Gloy lost another wheel. Although forced to run almost one complete lap on only three wheels and then pit for a replacement, Gloy still managed to finish fifth. His home track of Sears Point produced a second and gave him the lead in the points chase. He held the lead for one week. And then it expired at Riverside, along with that special developmental motor. At Las Vegas, Gloy was, perhaps, predictably, third in the race and third in the Championship.

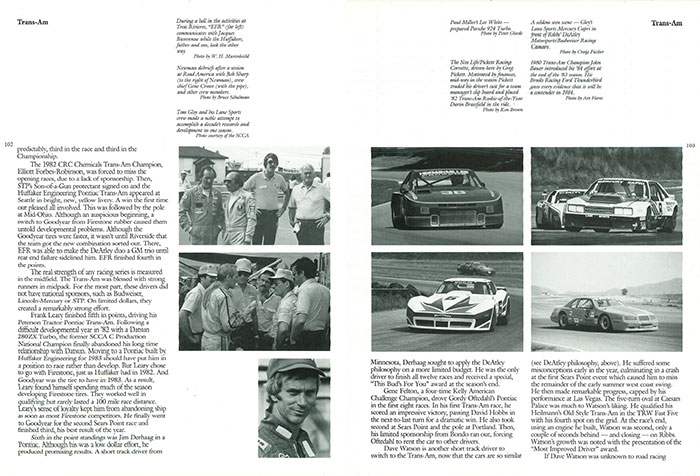

The 1982 CRC Chemicals Trans-Am Champion, Elliott Forbes-Robinson, was forced to miss the opening race, due to a lack of sponsorship. Then, STP’s Son-of-a-Gun protectant signed on and the Huffaker Engineering Pontiac Trans-Am appeared at Seattle in bright, new, yellow livery. A win the first time out pleased all involved. This was followed by the pole at Mid-Ohio. Although an auspicious beginning, a switch to Goodyear from Firestone rubber caused them untold developmental problems. Although the Goodyear tires were faster, it wasn’t until Riverside that the team got the new combination sorted out. There, EFR was able to make the DeAtley duo a GM trio until rear end failure sidelined him. EFR finished fourth in the points.

The real strength of any racing series in measured in the midfield. The Trans-Am was blessed with strong runners in mid-pack. For the most part, these drivers did not have national sponsors, such as Budweiser, Lincoln-Mercury or STP. On limited dollars, they created a remarkably strong effort.

Frank Leary finished fifth in points, driving his Peterson Tractor Pontiac Trans Am. Following a difficult developmental year in ’82 with a Datsun 280ZX Turbo, the former SCCA C Production National Champion finally abandoned his long time relationship with Datsun. Moving to a Pontiac built by Huffaker Engineering for 1983 should have put him in a position to race rather than develop. But Leary chose to go with Firestone, just as Huffaker had in 1982. And Goodyear was the tire to have in 1983. As a result, Leary found himself spending much of the season developing Firestone tires. They worked well in qualifying but rarely lasted a 100 mile race distance. Leary’s sense of loyalty kept him from abandoning ship as soon as most Firestone competitors. He finally went to Goodyear for the second Sears Point race and finished third, his best result of the year.

Sixth in the point standings was Jim Derhaag in a Pontiac. Although his was a low dollar effort, he produced promising results. A short track driver from Minnesota, Derhaag sought to apply the DeAtley philosophy on a more limited budget. He was the only driver to finish all twelve races and received a special “This Bud’s For You” award at the season’s end.

Gene Felton, a four-time Kelly American Challenge Champion, drive Gordy Oftedahl’s Pontiac in the first eight races. In his first Trans-Am race, he scored an impressive victory, passing David Hobbs in the next-to-last turn for a dramatic win. He also took second at Sears Point and the pole at Portland. Then, his limited sponsorship from Bondo ran out, forcing Oftedahl to rent the car to other drivers.

Dave Watson is another short track driver to switch to the Trans-Am, now that the cars are so similar (see DeAtley philosophy, above). He suffered some misconceptions early in the year, culminating in a crash at the first Sears Point event which caused him to miss the remainder of the early summer west coast swing. He then made remarkable progress, capped by his performance at Las Vegas. The five-turn oval at Caesars Palace was much to Watson’s liking. He qualified his Heilmann’s Old Style Trans Am in the TRW Fast Five with his fourth spot on the grid. At the race’s end, using an engine he built, Watson was second, only a couple of seconds behind – and closing – on Ribbs. Watson’s growth was noted with the presentation of the “Most Improved Driver” award.

If Dave Watson was unknown to road racing audiences, ninth-place finisher Paul Newman is well-known to audiences around the world. He was forced to fit a busy Trans-Am and SCCA GT-1 schedule around the production of a movie. The effort left him stretched thin, but earned him an Inspirational Award at the season’s end. In 1982, at Brainerd, Newman won the only Trans-Am he entered. For 1983, the Bob Sharp Racing organization built him a state-of-the-art tube frame Datsun 280ZX Turbo in which to contest the series. However, the team was limited to a pair of thirds as its best results. The Diet Coke Datsun was plagued by transmissions that proved too fragile in the face of impressive horsepower.

Lyn St. James finished tenth in points. The teammate to Tom Gloy in a Lane Sports Capri, her fourth in Seattle equaled the best Trans-Am finish posted by a woman. Also in a Ford SVO-backed Capri was Vern Smith. Smith, the ’82 IMSA Kelly Champion, was never able to get his ’83 program off the ground. In a Ford product, but not backed by Ford, was Rob McFarlin in the Kontrolle Shocks/Newslink Mustang. He, too, spent the season developing character and fortitude.

Paul Miller was the only consistent Porsche competitor, driving the 924 Turbo built by Holbert Racing. Miller’s best effort was posted at Seattle, where he had pole position and a second place finish.

Greg Pickett finished twelfth, driving a partial season. He claimed the pole in his Pickett Racing Corvette at the first Sears Point race, but the tires let him down. At Portland, he challenged Willy T. down to the last turn, losing by the season’s closest margin of victory, .6 of a second. Mid-season, Pickett turned the driver’s seat over to the ’82 Rookie of the Year, Darin Brassfield, and took on the responsibilities of Team Manager. Under his tutelage, young Brassfield learned some finesse, showing even more promise for the future.

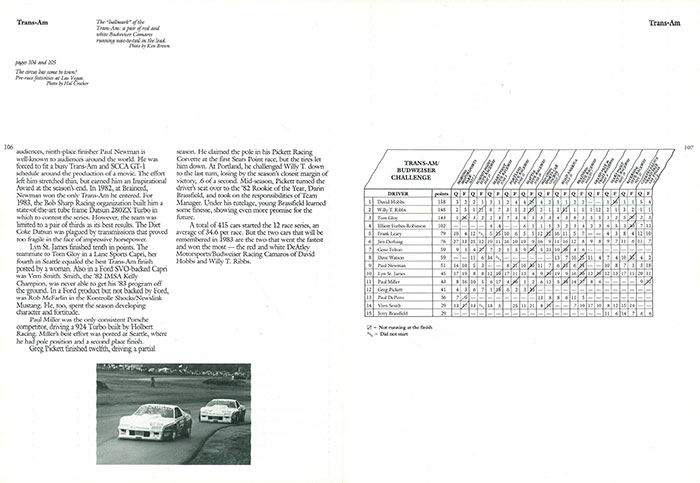

A total of 415 cars started the 12 race series, an average of 34.6 per race. But the two cars that will be remembered in 1983 are the two that went the fastest and won the most – the red and white DeAtley Motorsports/Budweiser Racing Camaros of David Hobbs and Willy T. Ribbs.